Python Tutorial

Setup

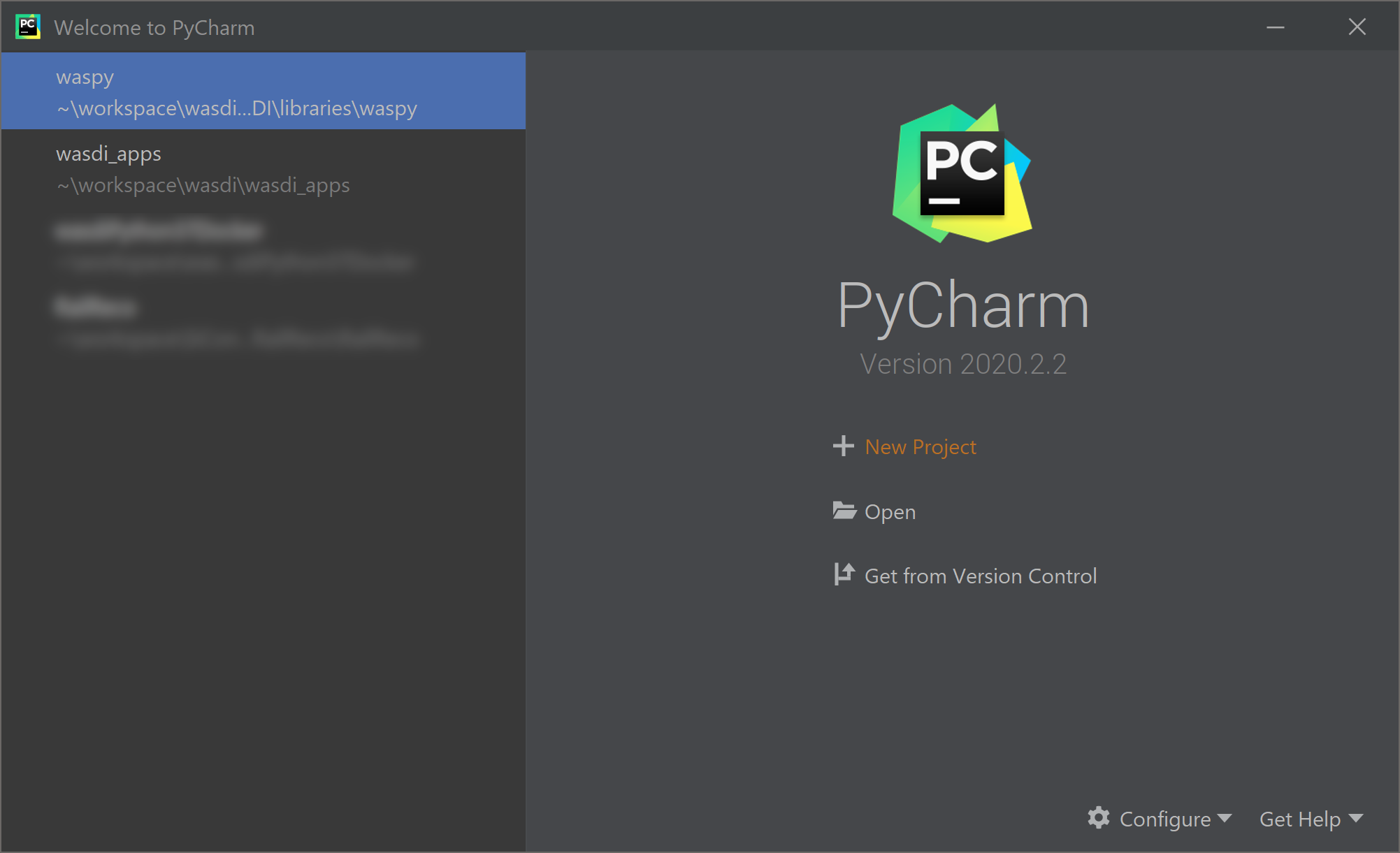

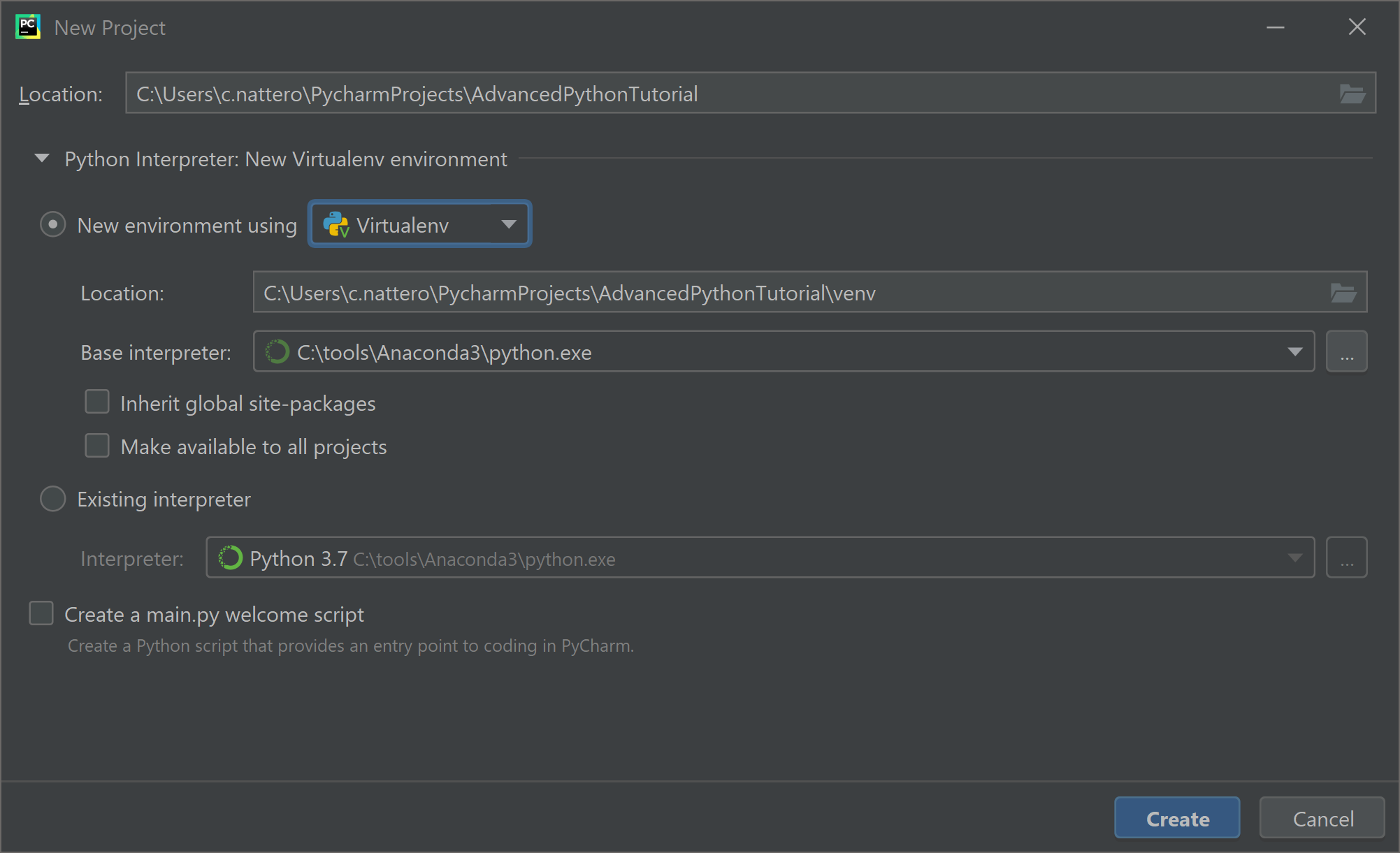

Open PyCharm and start a new project.

Call it “Advanced Python Tutorial” (or however you wish, just remember to be coherent). You may wish to create a new virtual environment (here we derive it from Python 3.8). Uncheck the option for creating a “main.py” welcome script (or, at least, remember to delete it later on).

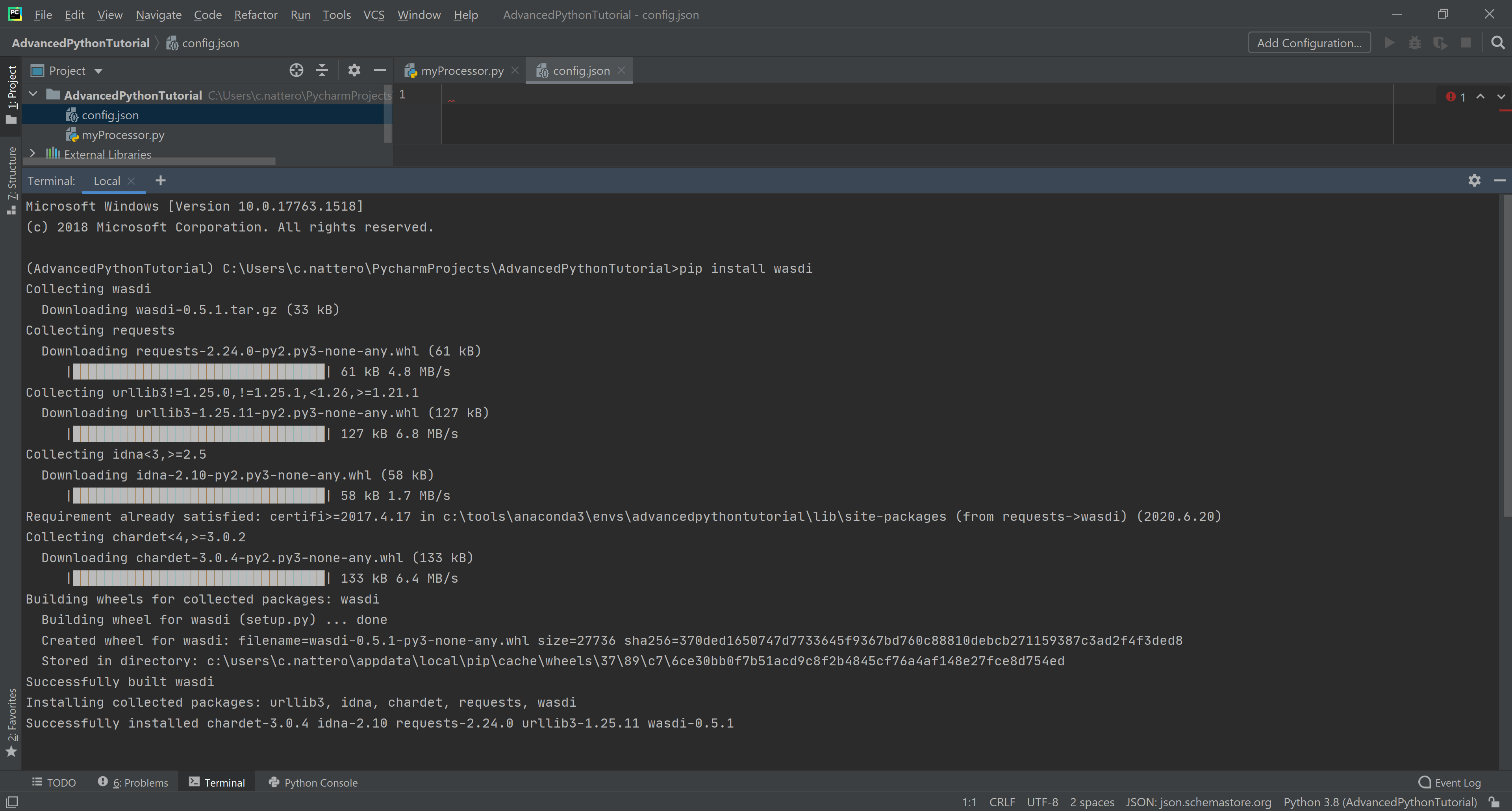

Let’s install the library we need. In the terminal write:

pip install wasdi

and press enter

hint: if you previously installed wasdi, you may wish to update it by adding the –upgrade flag, i.e.:

pip install --upgrade wasdi

Create first files

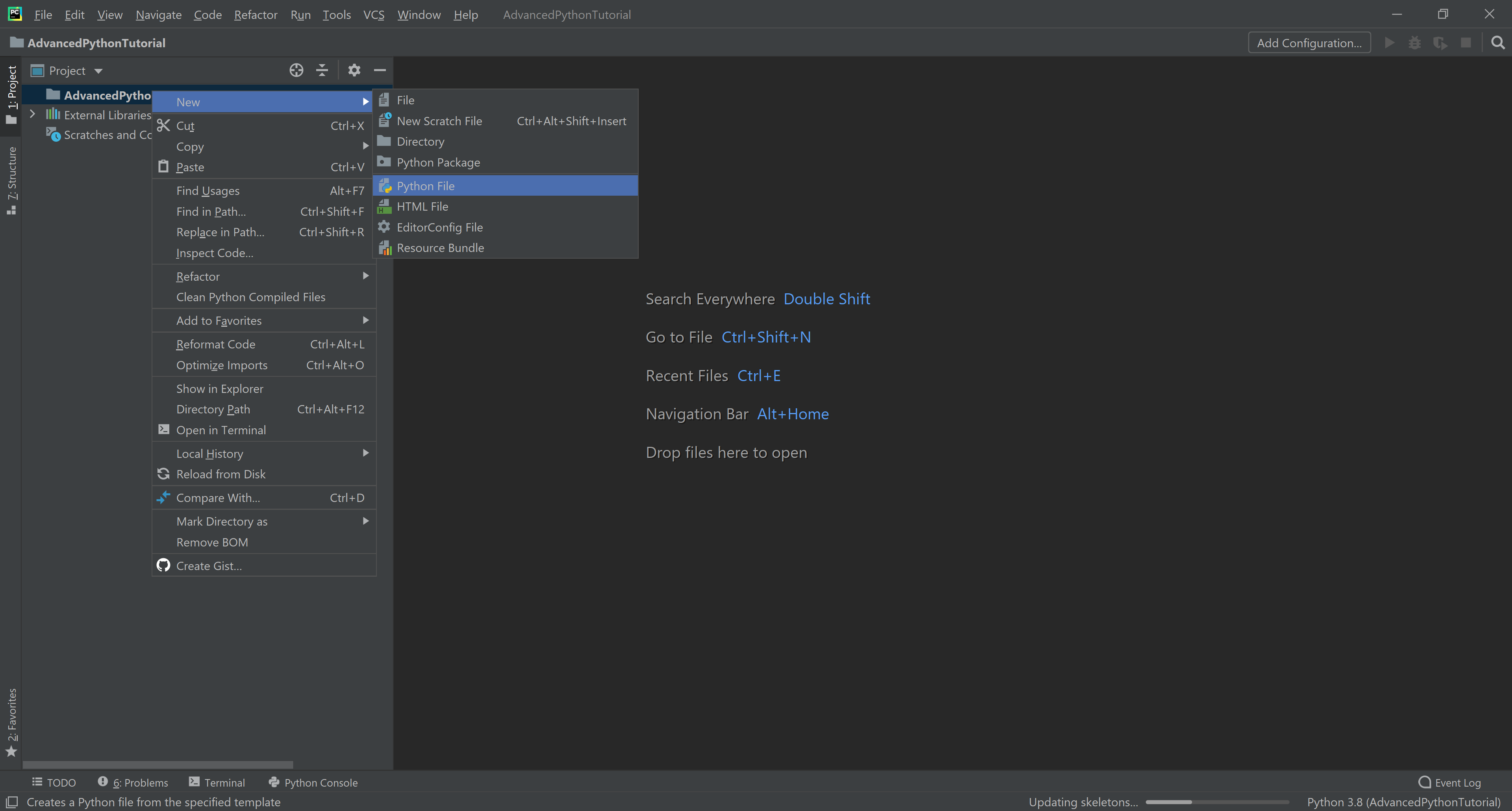

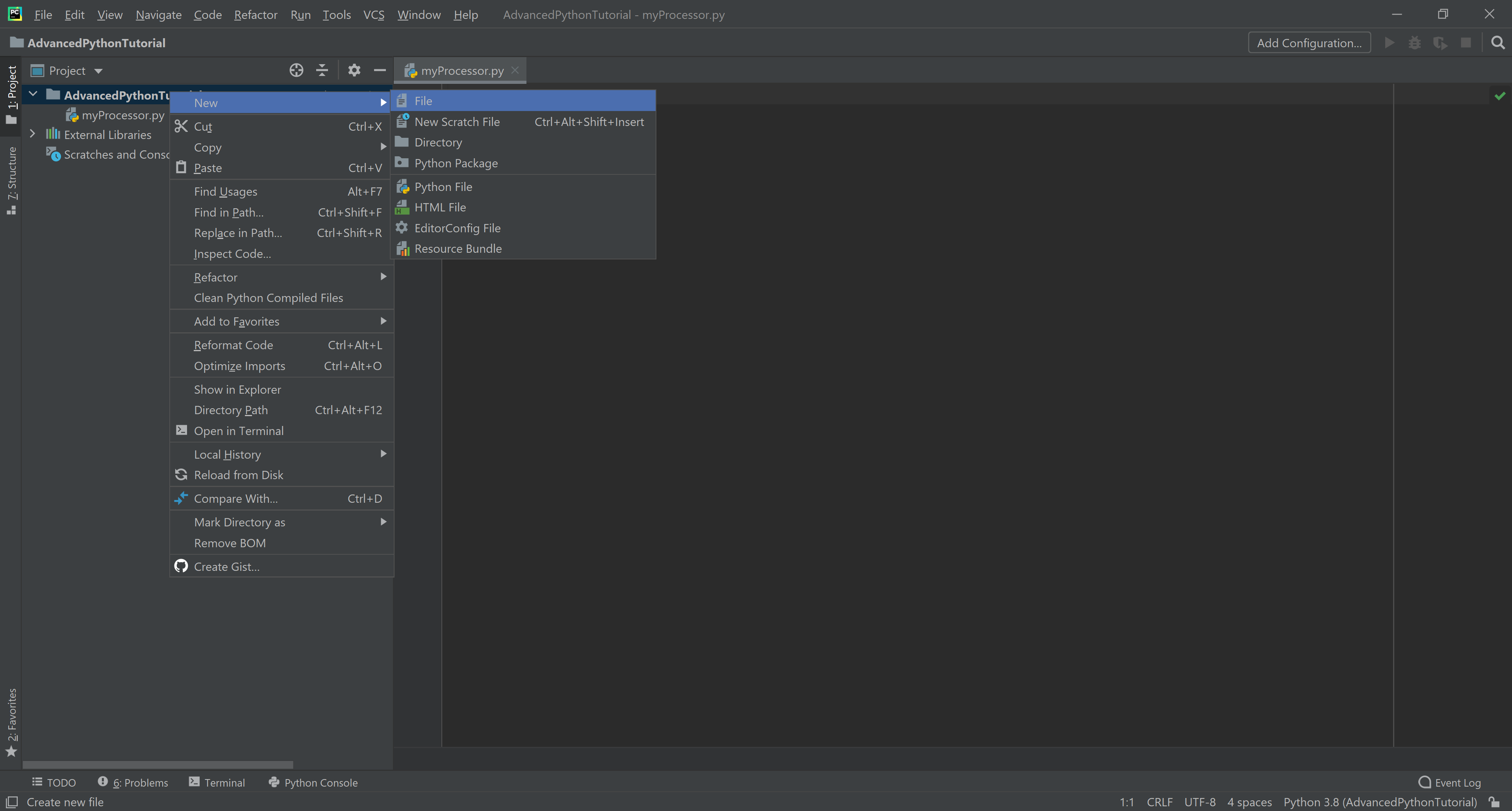

Now we need to create these two fundamental files (right click on the AdvancedPythonTutorial project icon, new -> …):

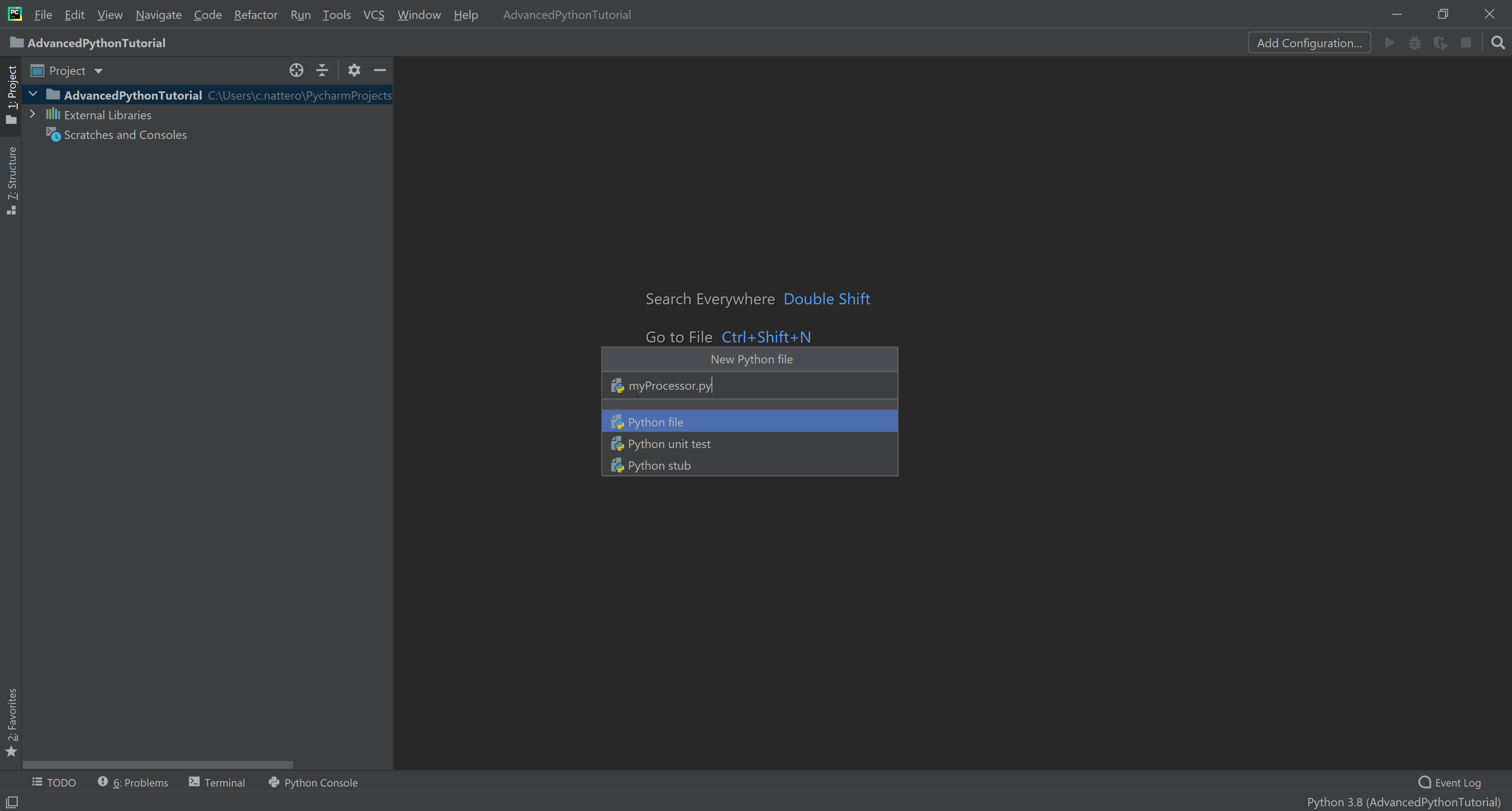

myProcessor.py: create a python file, then call it myProcessor.py

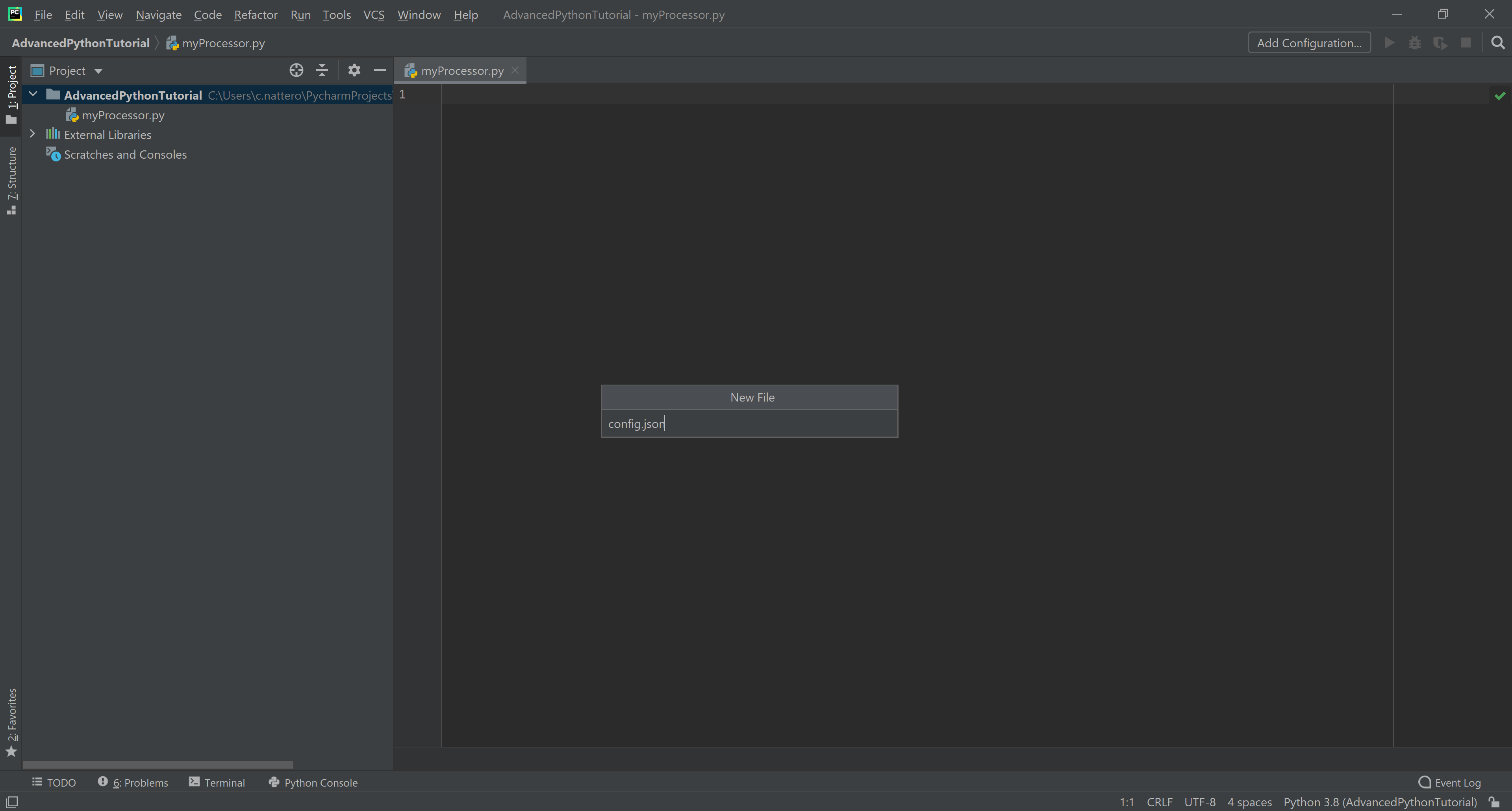

config.json: create a file, then call it config.json (PyCharm will recognize automatically it’s a JSON file)

Create python file

Create myProcessor.py

Create a file

Create config.json

Next, point your browser to wasdi.net, log in, make sure you see the workspaces page (otherwise click on the workspaces menu) and create a new workspace. Call it somehow, e.g., “AdvancedTutorialTest” (or however you want, just remember it and be coherent later on). Leave the browser open on that page, we’ll need it later on.

Create a workspace called AdvancedTutorialTest

First lines

Let’s begin by editing the config.json file. It’s a JSON file, containing the user credentials and some fundamental parameters to get you started:

{

"USER": "your user name here",

"PASSWORD": "your password here",

"WORKSPACE": "AdvancedTutorialTest"

}

NOTE: please, keep this file for yourself. You should never give this file to anyone else, and you do not need to upload to WASDI, as we’ll see later on. You just need this file in your project for working with the WASDI python library.

Now, open myProcessor.py, create a main and a method called run. The latter is required for WASDI to work (more on that later on).

Note: these are two requirements necessary to use WASDI:

have a python file called myProcessor.py

have a function called run() (no params) within myProcessor.py

After that, you can include as many python files as you need, no matter if they are organized in directories. You just need to have a myProcessor.py with a method run() as entry point.

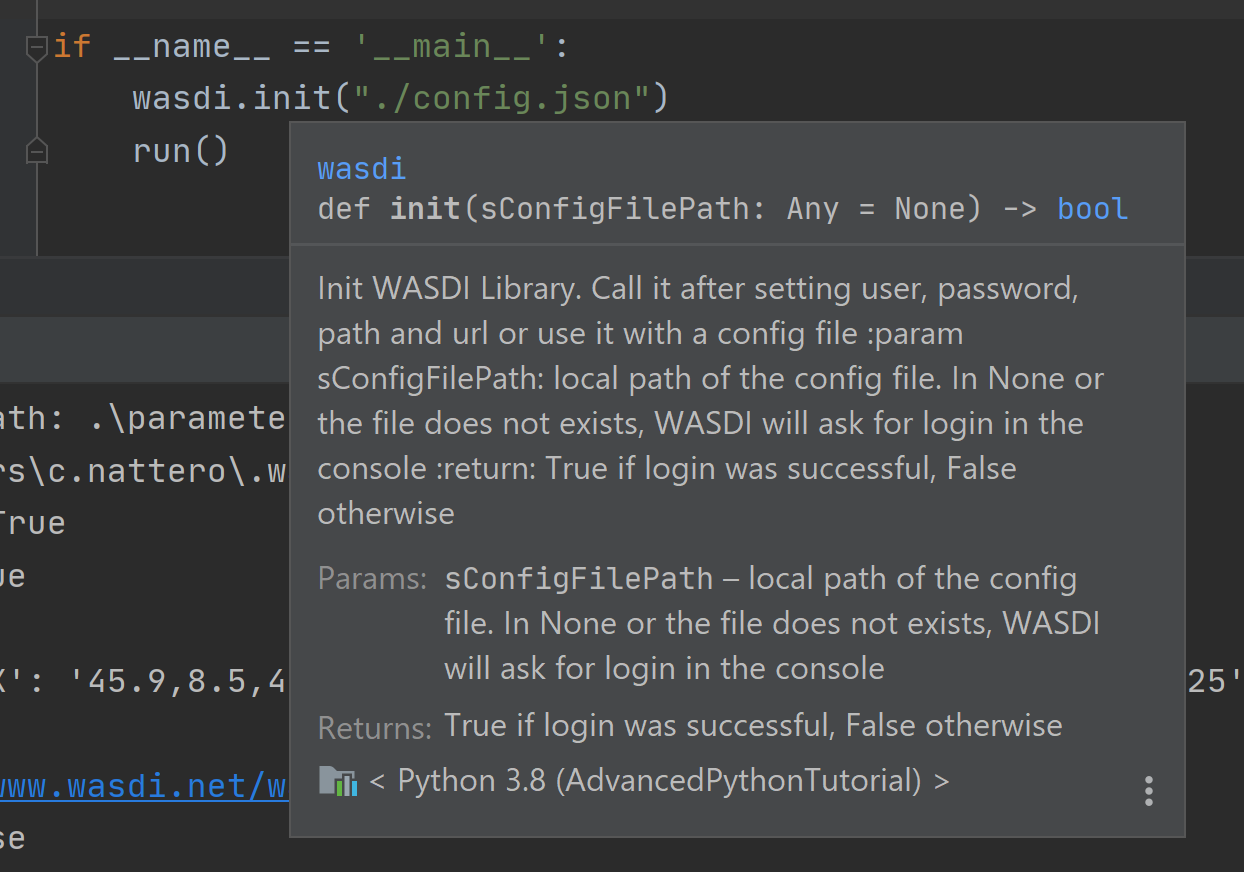

The main method will initiate the WASDI library and call the run method:

import wasdi

def run():

pass

if __name__ == '__main__':

wasdi.init("./config.json")

run()

As you can see, we call wasdi.init and pass the relative path of the config file to it.

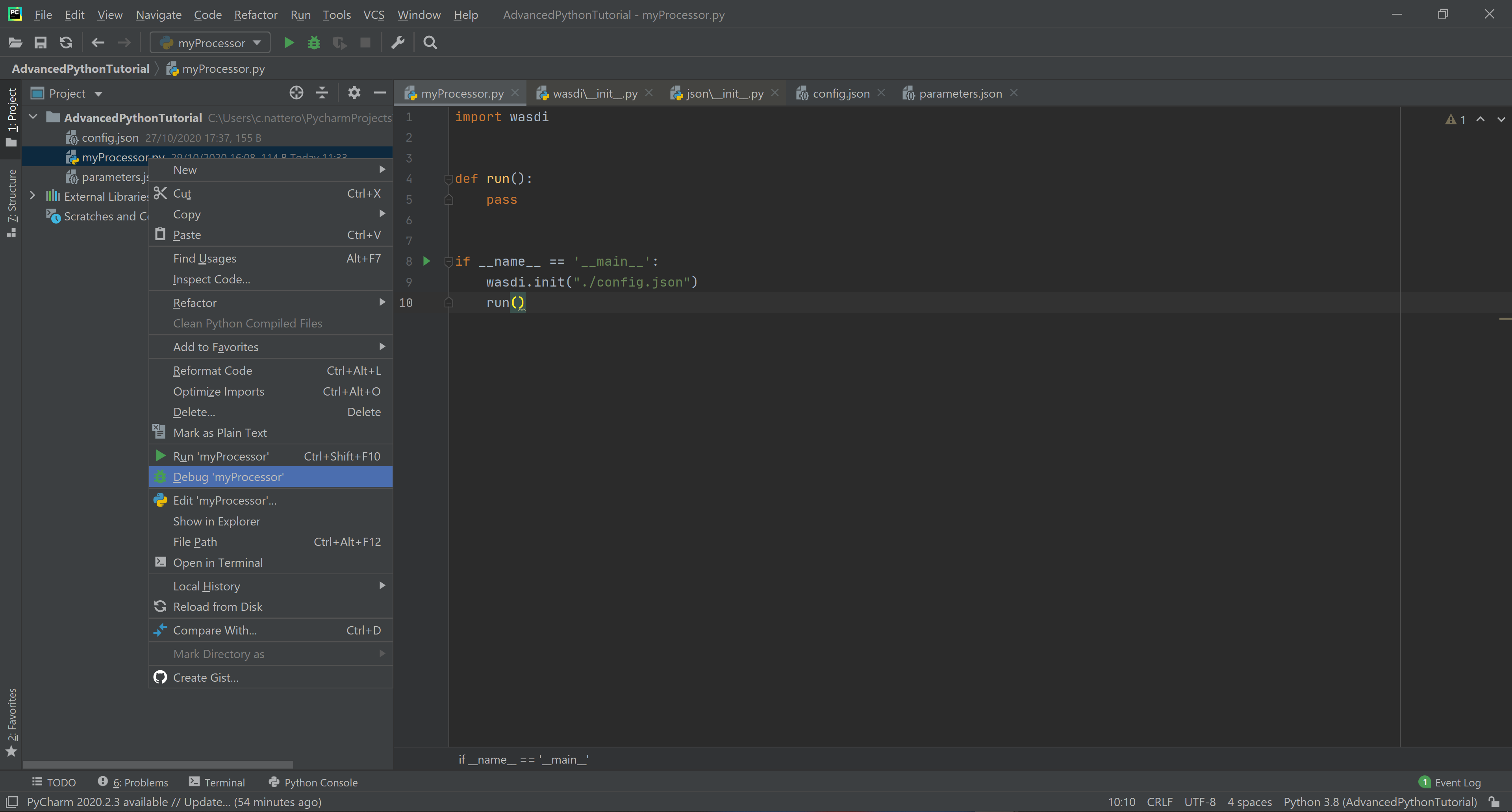

Let’s debug to see the effects of this. Note: if a file main.py was created automatically for you, remember to define another debug configuration. The easiest way to do so is by right clicking on your code and select Debug ‘myProcessor.py’.

If the setup is correct so far, we should see the output from the wasdi library that shows the initialization has gone well. Let’s see it more in details:

[INFO] _loadParams: wasdi could not load param file. That is fine, you can still load it later, don't worry

We’ll see to this later, for now we trust it and do not worry ;-)

[INFO] waspy.init: returned session is: 0d3f3ef1-f4c3-4202-9015-6ca17fc21cc7

Great, we authenticated and got a session (yours is going to be different)

[INFO] waspy.init: WASPY successfully initiated :-)

Good news

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: user: username@email.address

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: password: ***********

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: session id: 0d3f3ef1-f4c3-4202-9015-6ca17fc21cc7

Looks like our credentials worked. Yours username and session id will be different, and the password will not be shown. Pay attention, if you forget to insert the password, WASDI will ask you for it.

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: active workspace: 4f541d2c-4b29-445b-9869-9c8d185932ce

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: workspace owner: username@email.address

This code corresponds to the workspace we opened, i.e., AdvancedTutorialTest (it’s going to be different for you), next is the email address you used to register on WASDI

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: parameters file path: None

We did not provide a parameter file, we’ll see this later

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: base path: C:\Users\username\.wasdi\

This is the base path inside which WASDI will mirror the online file structure, creating one folder per workspace

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: download active: True

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: upload active: True

Downloads and uploads will happen automatically when necessary

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: verbose: True

Verbosity

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: param dict: {}

No params so far

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: proc id:

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: base url: http://www.wasdi.net/wasdiwebserver/rest

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: is on server: False

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: workspace base url: http://www.wasdi.net/wasdiwebserver/rest

More config info, which are fine

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: session is valid :-)

This is good

Process finished with exit code 0

And the debug finishes

WASDI Hello World

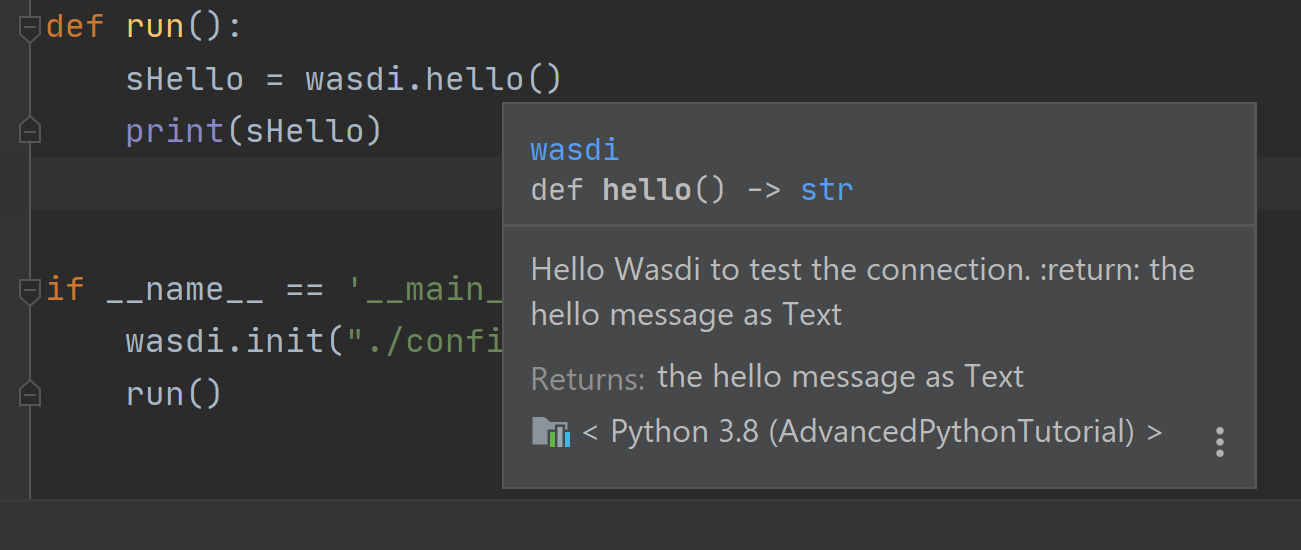

Now let’s try to call a WASDI API. There’s a hello world API just for these tests. Let’s change the run method code as follows:

def run():

sHello = wasdi.hello()

print(sHello)

Basically, the method wasdi.hello wraps a call to WASDI hello world API and returns the response, which we print on the next line, getting the following result:

{"boolValue":null,"doubleValue":null,"intValue":null,"stringValue":"Hello Wasdi!!"}

So that’s our first WASDI processor: we demonstrated we can authenticate and call an API using code.

Introducing parameters

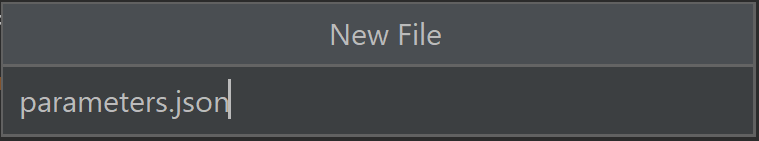

Now we’ll see how WASDI lets you handle the parameters for your processor. Let’s create a new file called parameters.json (Right click on the project, New -> File, name it parameters.json)

That’s another JSON file where the developer can set and/or simulate inputs for his processor. The idea is that WASDI processors can manipulate satellite images fed in input to create added-value products to be output. Parameters are those variables needed by the developer to retrieve input data and/or generate output data.

In the tutorial we are going to see some typical examples: the area of interest, the type of satellite data, a date or interval of dates. These parameters are defined in the file params.json During the development and the debug of the processor, the developer must write her/his input in this file. It’s like a dictionary: this way, the programmer decides what are the parameters and their syntax, and by assigning them a value she/he can test them.

Let’s try this example:

{

"NAME": "advanced python tutorial"

}

We also need to edit the config.json file to specify that we want to use parameters.json as the parameters file, and that’s done by adding the following line:

"PARAMETERSFILEPATH": "./parameters.json"

(please check that the JSON is valid, check especially your commas).

Now edit the run method and change it as follows:

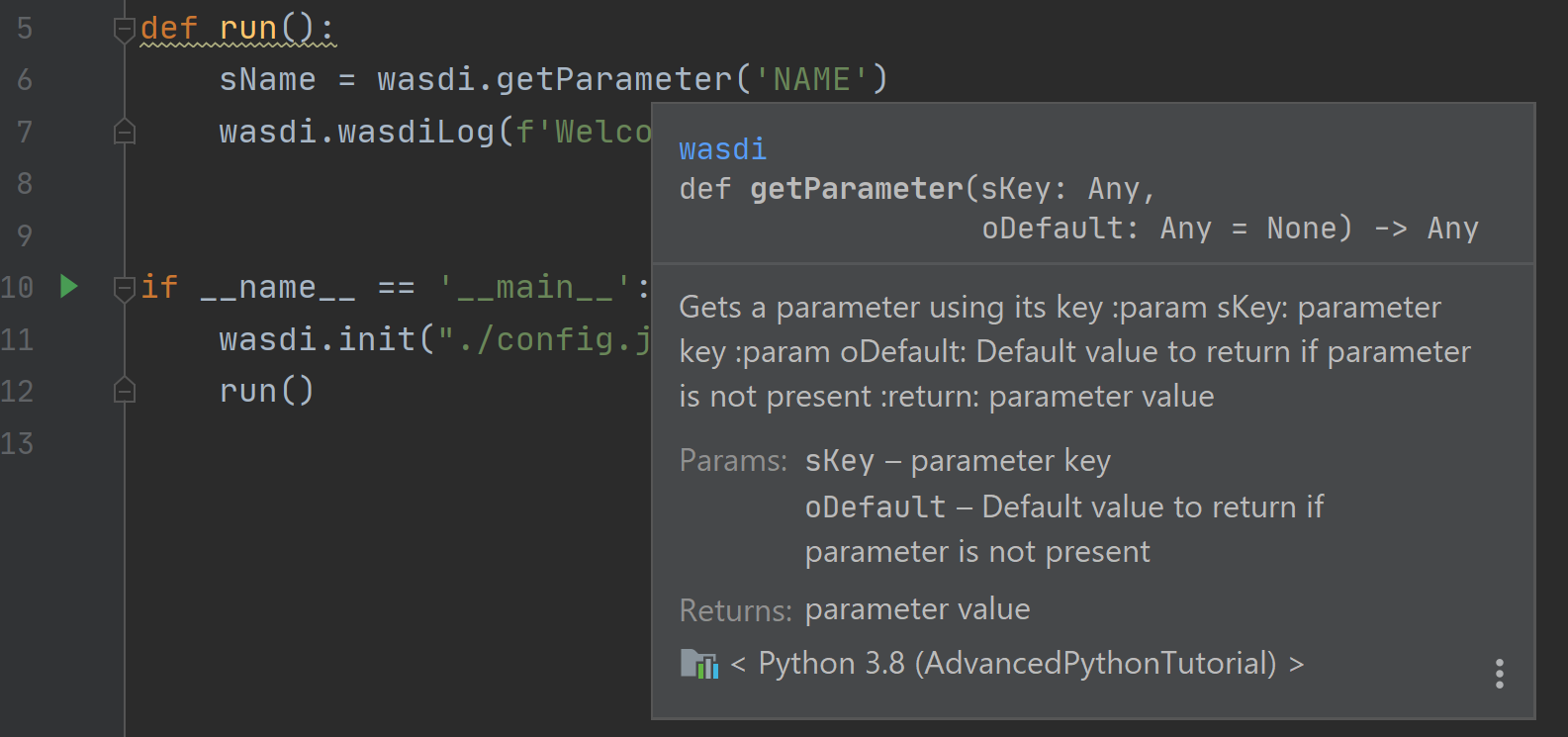

def run():

sName = wasdi.getParameter('NAME')

wasdi.wasdiLog(f'Welcome to the {sName}')

During the initialization, parameters are read from the specified file.

wasdi.getParameter is the method for reading a single parameter, and a default value can be specified.

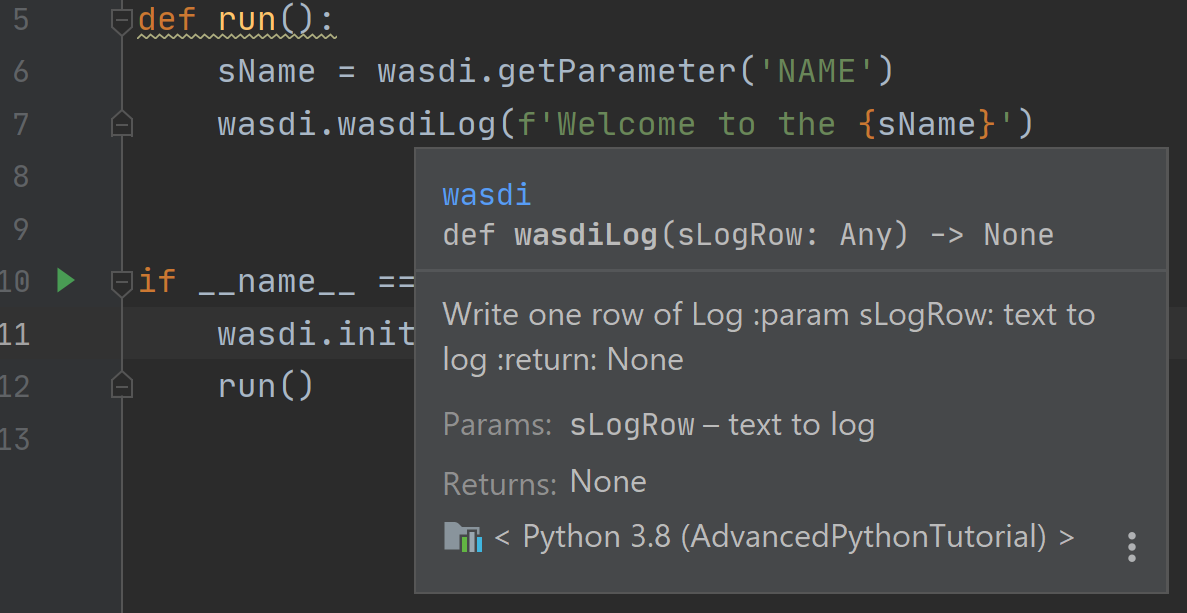

wasdi.wasdiLog is the utility for logging a line. It’s a print, locally, but when executed on the cloud, it prints a long line on the user interface.

Let’s debug it and we’re going to see, after the initialization output, the following line:

Welcome to the advanced python tutorial

Parameters can be of any type supported by the JSON format. When the processor will be deployed, the final user, or third party systems will be able to run it passing these parameters.

A more meaningful example

Let’s try another example. We want to write a processor that searches for Sentinel-2 images and uses them to create a RGB GeoTIFF file.

You can download the final code from here:

Step 1: read and validate parameters

Let’s change our parameters in parameters.json as follows:

{

"BBOX": "45.9,8.5,45.7,8.7",

"MAXCLOUD": "30",

"DATE": "2020-10-25",

"SEARCHDAYS": "20"

}

Now the file is in its final form, and you can download the file from here: parameters.json

These parameters represent, respectively:

the area of interest in the format “NORTH,WEST, SOUTH, EAST”

the maximum cloud coverage (percentage)

a date in which we want to search images

a maximum number of days to search back in time.

Now, edit the code of myProcessor.py

First of all, add the following imports:

from datetime import datetime

from datetime import timedelta

Next, modify the run method as follows:

def run():

# STEP 1: Read "real" parameters

sBBox = wasdi.getParameter("BBOX")

sDate = wasdi.getParameter("DATE")

sMaxCloud = wasdi.getParameter("MAXCLOUD", "20")

sSearchDays = wasdi.getParameter("SEARCHDAYS", "10")

sProvider = wasdi.getParameter("PROVIDER", "AUTO")

# L1

sImageType = wasdi.getParameter("IMAGETYPE", "S2MSI1C")

# L2

# sImageType = wasdi.getParameter("IMAGETYPE", "S2MSI2A")

# Check the Bounding Box: is needed

if sBBox is None:

wasdi.wasdiLog("BBOX Parameter not set. Exit")

wasdi.updateStatus("ERROR", 0)

return

# Split the bbox: it is in the format: NORTH, WEST, SOUTH, EAST

asBBox = sBBox.split(",")

if len(asBBox) != 4:

wasdi.wasdiLog("BBOX Not valid. Please use LATN,LONW,LATS,LONE")

wasdi.wasdiLog("BBOX received:" + sBBox)

wasdi.wasdiLog("exit")

wasdi.updateStatus("ERROR", 0)

return

# Ok is good, print it and convert in float

wasdi.wasdiLog("Bounding Box: " + sBBox)

fLatN = float(asBBox[0])

fLonW = float(asBBox[1])

fLatS = float(asBBox[2])

fLonE = float(asBBox[3])

iDaysToSearch = 10

try:

iDaysToSearch = int(sSearchDays)

except Exception as oEx:

wasdi.wasdiLog(f'Number of days to search not valid due to {repr(oEx)}, assuming 10 [' + str(sSearchDays) + "]")

# Check the date: assume now

oEndDay = datetime.today()

try:

# Try to convert the one in the params

oEndDay = datetime.strptime(sDate, '%Y-%m-%d')

except Exception as oEx:

# No good: force to yesterday

wasdi.wasdiLog(f'Date not valid due to {repr(oEx)}, assuming today')

oTimeDelta = timedelta(days=iDaysToSearch)

oStartDay = oEndDay - oTimeDelta

sEndDate = oEndDay.strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

sStartDate = oStartDay.strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

# Print the date

wasdi.wasdiLog("Search from " + sStartDate + " to " + sEndDate)

# Check the cloud coverage

sCloudCoverage = None

if sMaxCloud is not None:

sCloudCoverage = "[0 TO " + sMaxCloud + "]"

wasdi.wasdiLog("Cloud Coverage " + sCloudCoverage)

else:

wasdi.wasdiLog("Cloud Coverage not set")

The code reads, validates and manipulates the parameters.

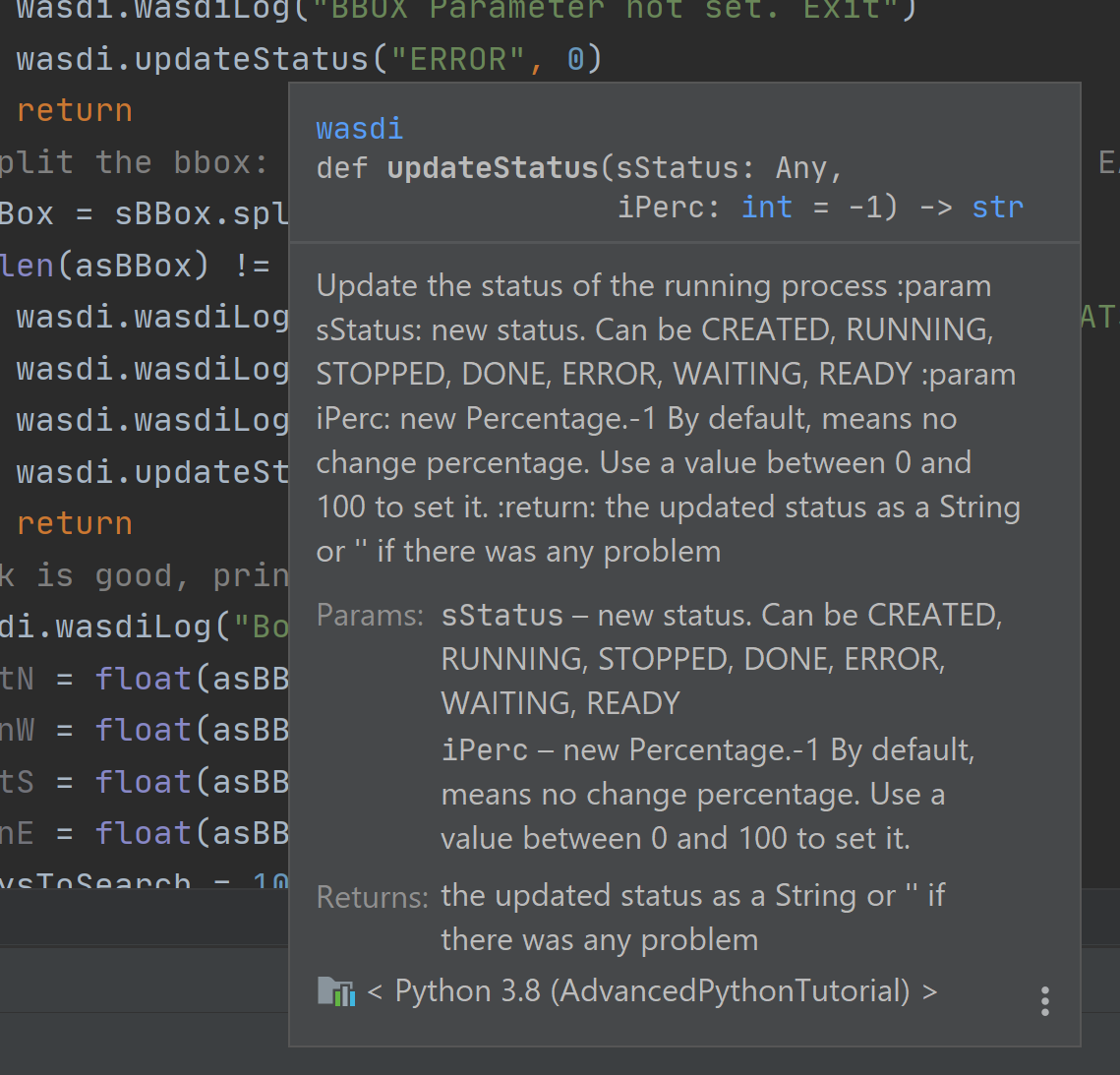

updateStatus is another primitive: it allows to update the process status and the progress (percent) of its execution.

Each WASDI process has a status among the following:

CREATED: a newly created process, waiting to be executed

RUNNING: a process that is being executed

WAITING: a process that was running and is now waiting for another resource, and has been put on hold for this reason

READY: a process that obtained the resource for which it was WAITING and is now waiting for the WASDI scheduler to continue executing it

DONE: process that completed successfully

ERROR: the execution encountered some error that prevented the process from completing correctly

STOPPED: process stopped by the user or by another processor.

Let’s run it and, if everything is properly set, we will see the usual output, but now we are going to see these two lines too (one is different, the other is new):

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: parameters file path: .\parameters.json

[INFO] waspy.printStatus: param dict: {'BBOX': '45.9,8.5,45.7,8.7', 'MAXCLOUD': '30', 'DATE': '2020-10-25', 'SEARCHDAYS': '10'}

Also, we are going to see our logs:

Bounding Box: 45.9,8.5,45.7,8.7

Search from 2020-10-15 to 2020-10-25

Cloud Coverage [0 TO 30]

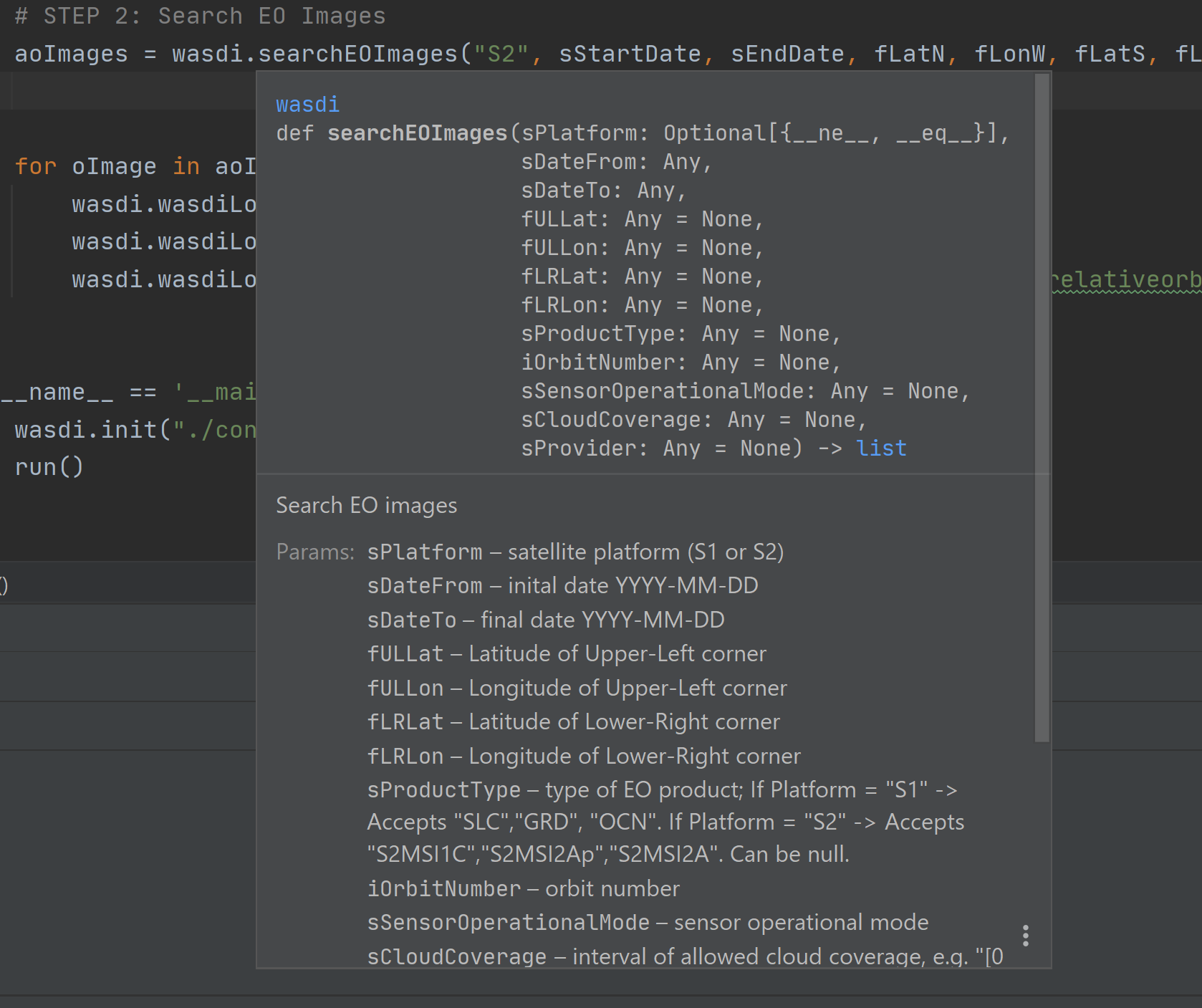

Step 2: search the catalogs for EO data

Add the following lines to the run method to search for EO images

# STEP 2: Search EO Images

aoImages = wasdi.searchEOImages("S2", sStartDate, sEndDate, fLatN, fLonW, fLatS, fLonE, sImageType, None, None, sCloudCoverage, sProvider)

for oImage in aoImages:

wasdi.wasdiLog("Image Name WITHOUT Extension:" + oImage['title'])

wasdi.wasdiLog("Image Name WITH Extension:" + oImage['fileName'])

The method searcheEOimages allows filtering for area of interest (bounding box), mission, product type, orbit number, sensor operational mode and cloud coverage (when applicable to the data type). A more advanced usage allows to specify the provider to use, but that’s beyond the scope of this tutorial.

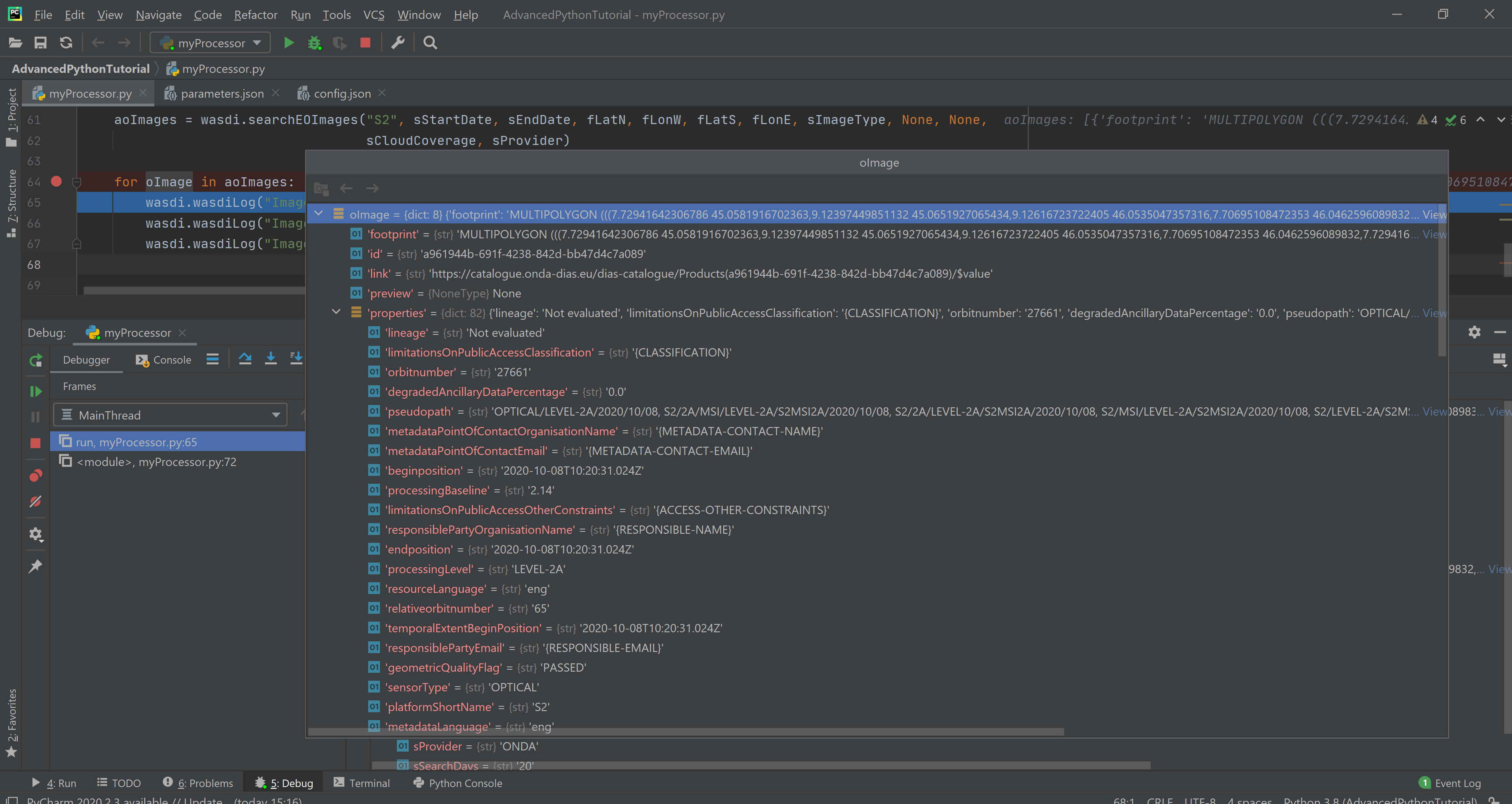

The method returns a list of objects, one per image. Each of these object is in turn a dictionary, describing the image: it contains every propriety returned by the search, such as, for example:

footprint

beginPosition

endPosition

cloudShadowPercentage

relativeOrbitNumber

orbitDirection

There are many more, and we can see them debugging the code. Please note that the number and type of these parameters depends on the data provider.

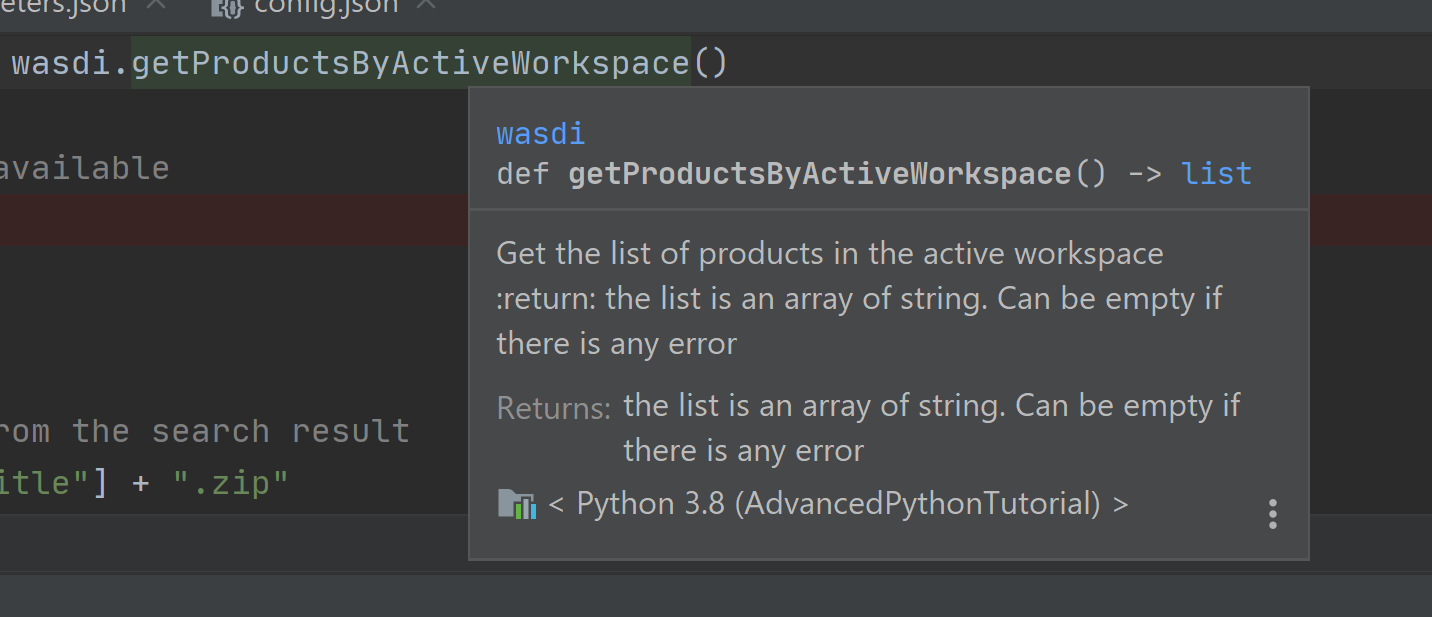

Step 3: import EO images in the workspace

Now we want to import selected images in the workspace.

# STEP 3: Import EO Images in the workspace

# Get the list of products in the workspace

asAlreadyExistingImages = wasdi.getProductsByActiveWorkspace()

# List of images not yet available

aoImagesToImport = []

# For each found image

for oImage in aoImages:

# Get the file Name from the search result

sFileName = oImage["fileName"]

# If the file name is not yet in the workspace

if sFileName not in asAlreadyExistingImages:

# Add it to the list of images to import

aoImagesToImport.append(oImage)

# If there are images to import

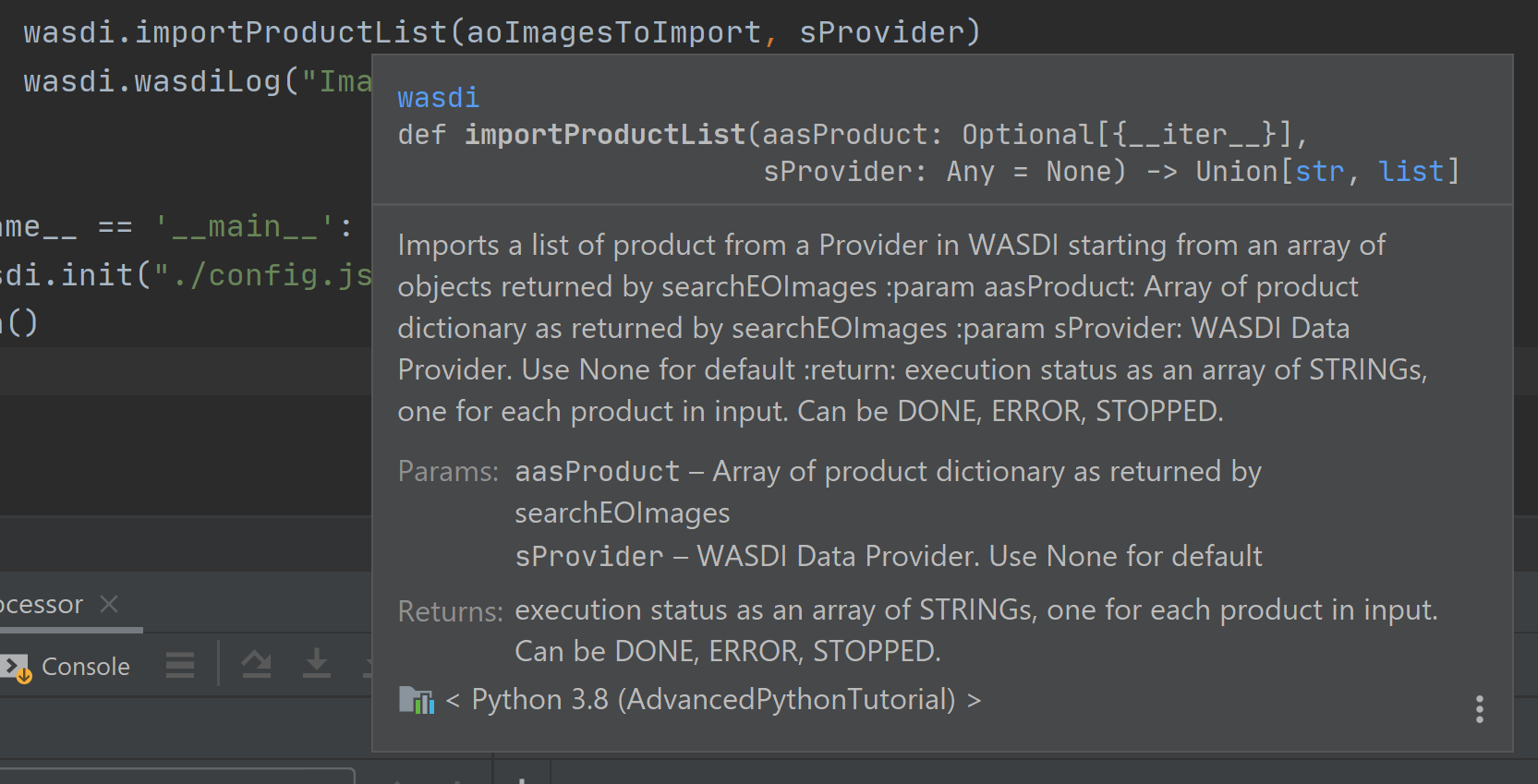

if len(aoImagesToImport) > 0:

# Trigger the import of the images

wasdi.importProductList(aoImagesToImport, sProvider)

wasdi.wasdiLog("Images Imported")

Here we check, for each image, if it is not yet in the workspace. It’s not strictly necessary, as it is handled by WASDI, but in this way we optimize the process: if an image is not already present, then we add it to the list of images to be imported, and finally we retrieve them from the provider.

The method wasdi.getProductsByActiveWorkspace returns a string array with the names of files in the workspace.

To compare the search results with the files in the workspace we need to obtain the file name. This can depend on the provider and on the image type but, for instance, with every Sentinel image it’s easily reproduced with:

sFileName = oImage["title"] + ".zip"

Next, wasdi.importProductList allows to import a batch of images from the specified provider.

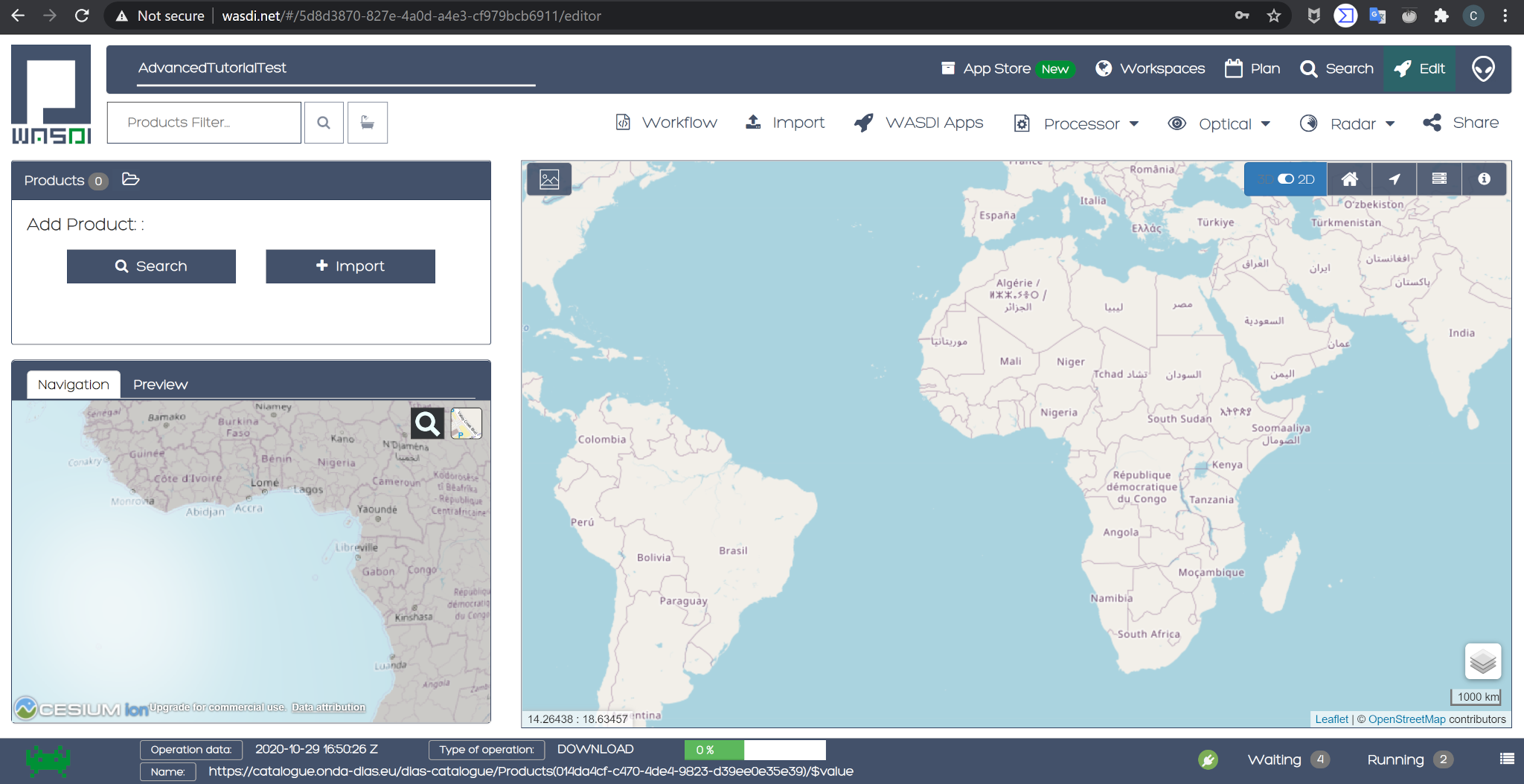

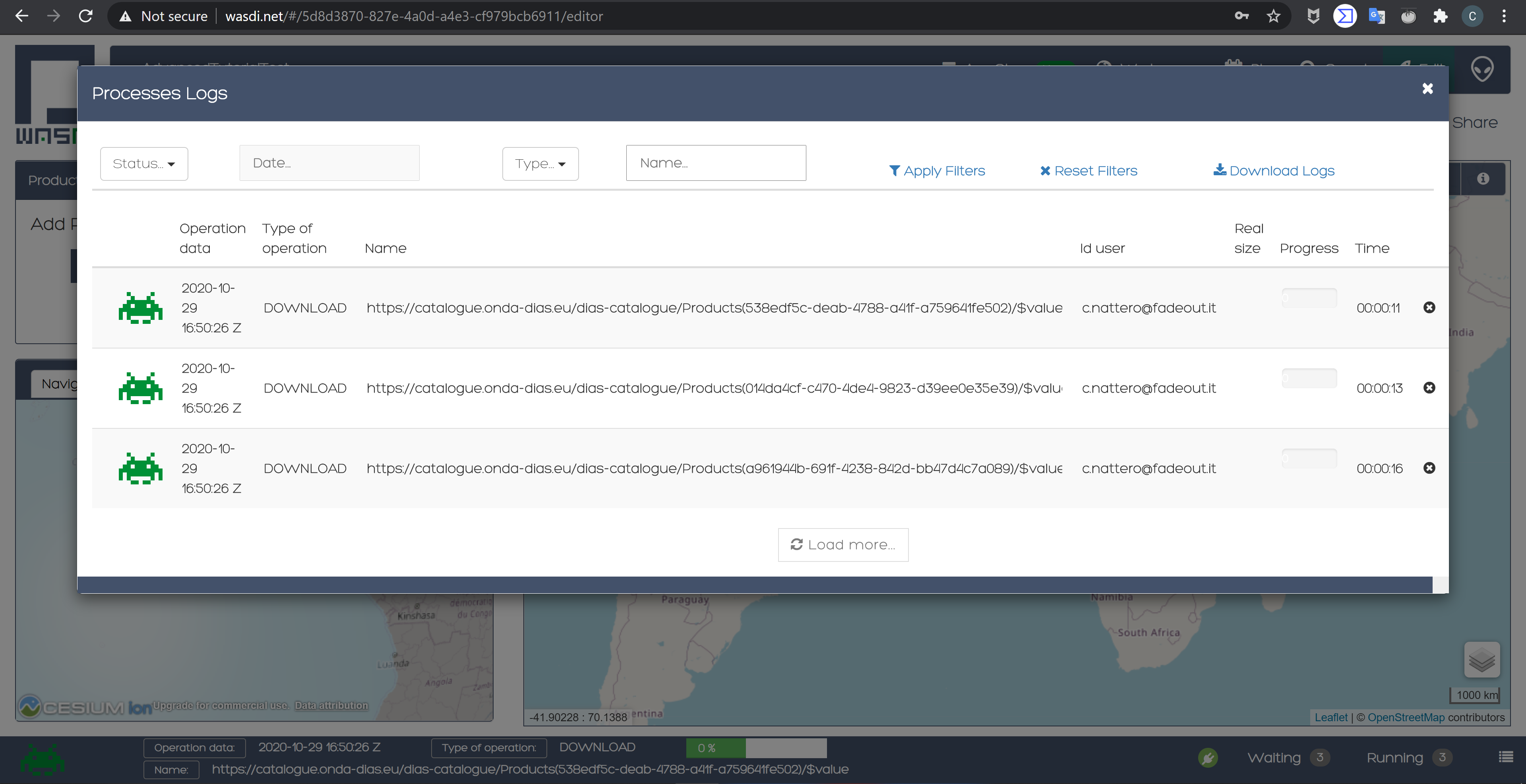

WASDI will take control of the process and handle the task by queuing the requests in the background. The entire operation runs in the cloud. It will take a while, and during that time you will not be able to control the debugger. However, if you get back to your browser (did you remember to leave it open on the workspace editor?) you will be able to check the status of the operation.

If you click on the list icon in the bottom right corner of the screen, you can also view details for each operation in progress:

Step 4: create an 8-bit RGB GeoTIFF out of a Sentinel-2 image

Now we want to open one of those Sentinel-2 images, extract bands for Red, Green and Blue (RGB) and use them to construct an RGB GeoTIFF. We are going to use numpy and GDAL. GDAL is a set of tool for working with geo referenced images. You may need to install it in your environment. In that case, execute

pip install GDAL

in your terminal.

Make sure you have the latest version of Microsoft Visual C++ Build Tools installed, you can download the installer from this link https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/it/thank-you-downloading-visual-studio/?sku=BuildTools&rel=16.

If you get some error, try to install GDAL following these steps:

Download the wheel from (https://www.lfd.uci.edu/~gohlke/pythonlibs/#gdal) the website has many libraries that are very useful.

1.1 Pay attention to the last part of the wheel to choose the correct one suitable for your PC, for example check if it is 64 or 32 bit.(For more information check: https://realpython.com/python-wheels/#what-is-a-python-wheel).

Open the Windows Terminal (CMD) and type “pip install (the path the wheel located in)”.

Add the following imports:

import numpy

import zipfile

import os

from osgeo import gdal

Now we need a way to extract the three bands from the Sentinel-2 image.

run()

Here in the following you can find the lines to add to the run method. Beware, there are two calls to two methods, extractBands and stretchBandValues, which will not work: we are going to implement them in a moment, keep reading. Here’s the snippet:

# STEP 4: From the S2 image create a 8-bit RGB GeoTiff

# Get again the list of images in the workspace:

asAvailableImages = wasdi.getProductsByActiveWorkspace()

# Check if we have at least one image

if len(asAvailableImages) <= 0:

# Nothing found

wasdi.wasdiLog("No images available, nothing to do.")

wasdi.updateStatus("DONE", 100)

return

# Initialize the image to process as None

sImageToProcess = None

# Take the first S2 image

for sImg in asAvailableImages:

if sImg.startswith("S2):

sImageToProcess = sImg

break

if sImageToProcess is None:

wasdi.wasdiLog("Cannot find our S2 image in the workspace")

wasdi.updateStatus("DONE", 100)

return

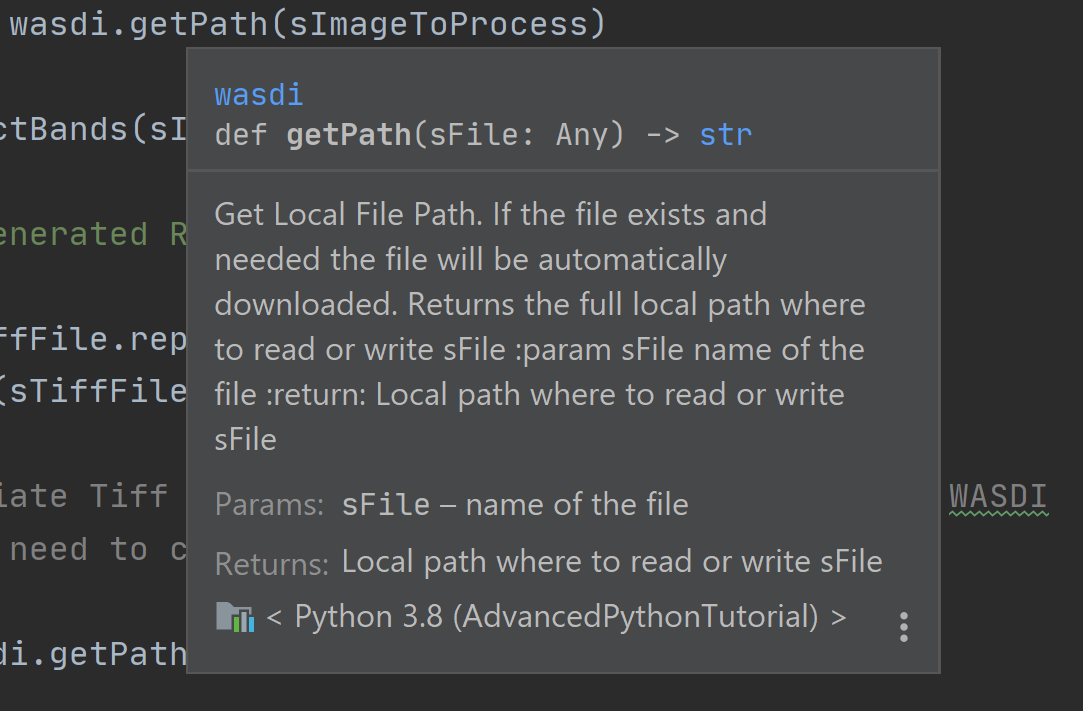

# Get the local path of the image: this is one of the key-feature of WASDI

# The system checks if the image is available locally and, if it is not, it will download it

sLocalImagePath = wasdi.getPath(sImageToProcess)

sTiffFile = extractBands(sImageToProcess, sImageType)

wasdi.wasdiLog("Generated RGB Tiff: " + sTiffFile)

sOutputFile = sTiffFile.replace(".tif", "_rgb.tif")

stretchBandValues(sTiffFile, sOutputFile)

# Delete intermediate Tiff File: NOTE this has not been added to WASDI

# so there is the need to clean only the physical file

try:

os.remove(wasdi.getPath(sTiffFile))

except:

wasdi.wasdiLog("Error removing " + sTiffFile)

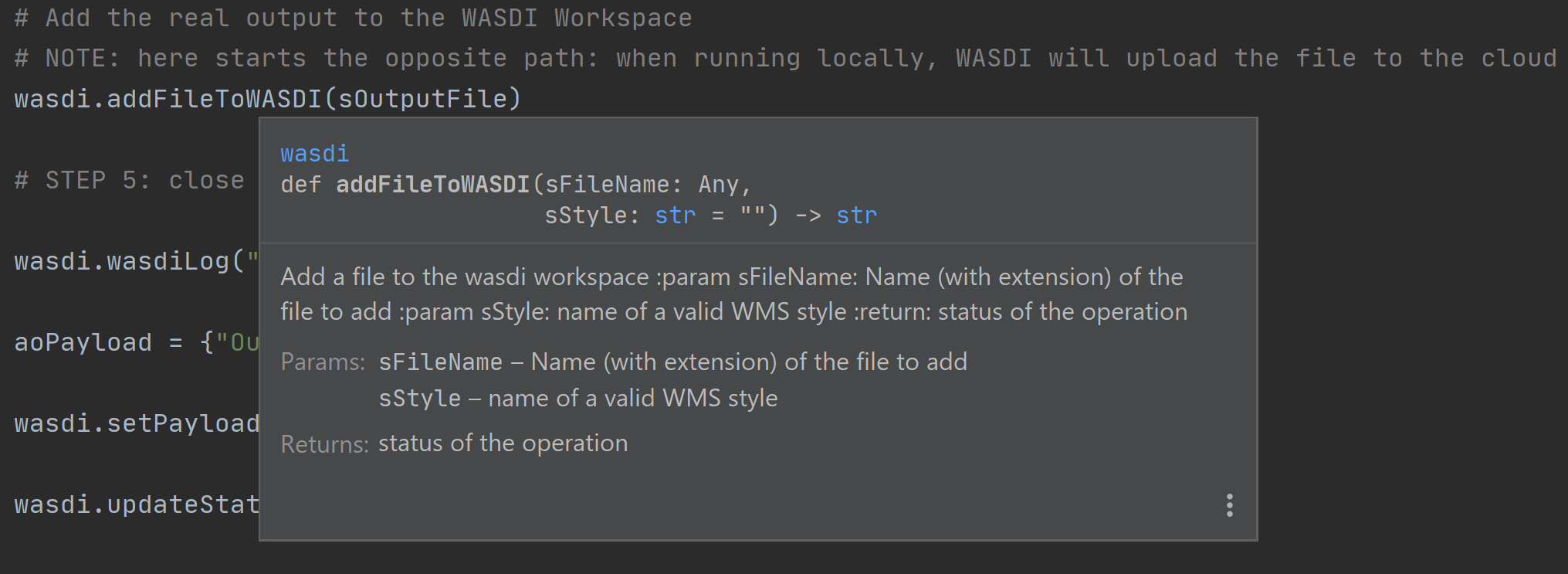

# Add the real output to the WASDI Workspace

# NOTE: here starts the opposite path: when running locally, WASDI will upload the file to the cloud

wasdi.addFileToWASDI(sOutputFile)

You noticed the call to wasdi.getPath: those are very important lines, since it’s one of the basis on which we built the library. Up to now, every file path we used was relative (we actually used just the file name). The key concept here is that a file is not needed locally until it is open (think of it as a kind of lazy access). WASDI’s getPath method is used to translate a file name to an absolute path. When the developer tries to access the file, WASDI understands if it exists in the platform or not and returns, depending on the case, either the local absolute path in which to create a file that does not yet exist, or the local absolute path from which it is possible to read the searched file. In this second case, the system automatically understands that the developer is currently working locally and downloads the required file automatically. As soon as the file is available, the control returns to the IDE, and the debug can proceed.

Note: in general, downloading file is not what we want and, once the processor will be deployed on the cloud, it is not going to happen any more: we will thus be able to process also large batches of EO data. However, as long as we are developing, we need to download some images, just to check that everything works as we expect it to work. The WASDI python library is smart enough to understande whether the code is running on our PC or in the cloud, and change behavior transparently and automatically.

The call to addFileToWasdi is worth a mention too. The method adds the file entry to the WASDI system so that it can be accessed and further used by WASDI. Again, this call has a double way of working: on the cloud, it simply adds the product to the WASDI data collection; when executed locally, the library realizes automatically that the file is missing on the platform and uploads.

Note: we do not like uploads either. However we decided to implement this functionality because being able to test our processor from end to end to is fundamental. So, uploads will take place only during development, whereas they will not be necessary when the processor will run on the cloud.

Next, we need to create the following two methods that we wish to call:

extractBands

stretchBandValues

extractBands

This method gets a collection of bands, and extracts them as a virtual GeoTIFF from the Sentinel-2 image, and finally creates a GeoTIFF with the extracted bands.

def extractBands(sFile, sImageType):

try:

sOutputVrtFile = sFile.replace(".zip", ".vrt")

sOutputTiffFile = sFile.replace(".zip", ".tif")

# Get the Path

sLocalFilePath = wasdi.getPath(sFile)

sOutputVrtPath = wasdi.getPath(sOutputVrtFile)

sOutputTiffPath = wasdi.getPath(sOutputTiffFile)

# Band Names for S2 L2

asBandsJp2 = ['B04_10m.jp2', 'B03_10m.jp2', 'B02_10m.jp2']

if sImageType != "S2MSI2A":

# Band Names for S2 L1

asBandsJp2 = ['B04.jp2', 'B03.jp2', 'B02.jp2']

with zipfile.ZipFile(sLocalFilePath, 'r') as sZipFiles:

asZipNameList = sZipFiles.namelist()

asBandsS2 = [name for name in asZipNameList for band in asBandsJp2 if band in name]

asBandsZip = ['/vsizip/' + sLocalFilePath + '/' + band for band in asBandsS2]

asOrderedZipBands = []

for sBand in ['B04', 'B03', 'B02']:

for sZipBand in asBandsZip:

if sBand in sZipBand:

asOrderedZipBands.append(sZipBand)

break

gdal.BuildVRT(sOutputVrtPath, asOrderedZipBands, separate=True)

# , options="-tr " + sResolution + " " + sResolution

gdal.Translate(sOutputTiffPath, sOutputVrtPath)

os.remove(sOutputVrtPath)

return sOutputTiffFile

except Exception as oEx:

wasdi.wasdiLog(f'extractBands EXCEPTION: {repr(oEx)}')

return ""

Sentinel-2 images contain Blue in band 2, Green in band 3, and Red in band 4. Here we extract them from the original file, save them into a virtual GeoTIFF (a .vrt file), and then we create a GeoTIFF. Finally, we can delete the virtual file, and return the name of the GeoTIFF RGB file we just created

stretchBandValues

Here, using numpy, we manipulate the bands. Add the following method to myProcessor.py:

def stretchBandValues(sOutputTiffPath, sStretchedOutputFile):

oDataset = gdal.Open(wasdi.getPath(sOutputTiffPath))

if not oDataset:

wasdi.wasdiLog("Impossible to get Dataset from " + sOutputTiffPath)

return ""

[iCols, iRows] = oDataset.GetRasterBand(1).ReadAsArray().shape

oDriver = gdal.GetDriverByName("GTiff")

oOutDataFile = oDriver.Create(wasdi.getPath(sStretchedOutputFile), iRows, iCols,

oDataset.RasterCount, gdal.GDT_Byte, ['COMPRESS=LZW', 'BIGTIFF=YES'])

# sets same geotransform as input

oOutDataFile.SetGeoTransform(oDataset.GetGeoTransform())

# sets same projection as input

oOutDataFile.SetProjection(oDataset.GetProjection())

for iBand in range(oDataset.RasterCount):

iBand += 1

oBand = oDataset.GetRasterBand(iBand)

if oBand is None:

wasdi.wasdiLog("BAND " + str(iBand) + " is None, jump")

continue

adBandArray = numpy.array(oBand.ReadAsArray())

adBandArray[adBandArray > 5000] = 5000

adBandArray = adBandArray.astype(float)

adBandArray *= 0.051

adBandArray = adBandArray.astype(int)

oOutDataFile.GetRasterBand(iBand).WriteArray(adBandArray)

oOutDataFile.GetRasterBand(iBand).SetNoDataValue(0)

oBand = None

# saves to disk!!

oOutDataFile.FlushCache()

wasdi.wasdiLog("Saved " + sStretchedOutputFile)

This method opens the tif file we just created, reads the bands as numpy arrays, and cuts each band empirically at a value of 5000, then scales their values down into [0, 255]. The file is saved to disk and its name is returned.

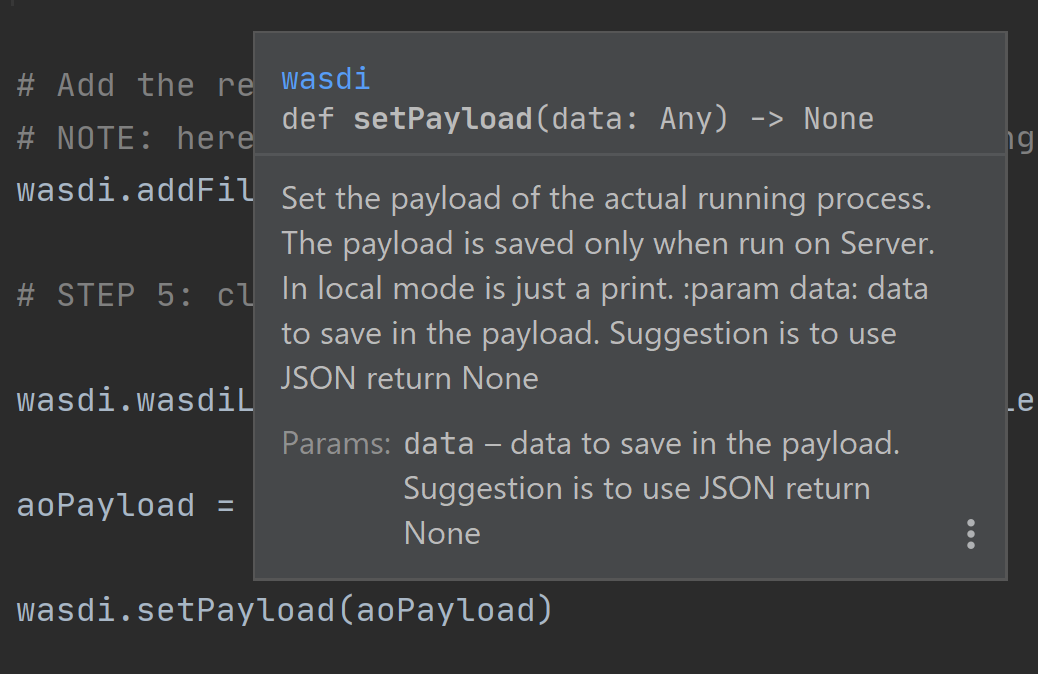

Step 5: close the WASDI processor

We’re almost done! Add the remaining part to myProcessor.py:

# STEP 5: close the processor

wasdi.wasdiLog("Created output file " + sOutputFile)

aoPayload = {"OutputFile": sOutputFile}

wasdi.setPayload(aoPayload)

wasdi.updateStatus("DONE", 100)

Here we set a payload for the processor. The payload consists of the output parameters, i.e., a dictionary that can be retrieved later in form of a JSON object.

To retrieve that payload you can use wasdi.getProcessorPayloadAsJson and pass the processID as argument. You can obtain the process ID from the UI or programmatically: it’s given in output when launching another processor. Finally, we set the status to DONE before closing the processing.

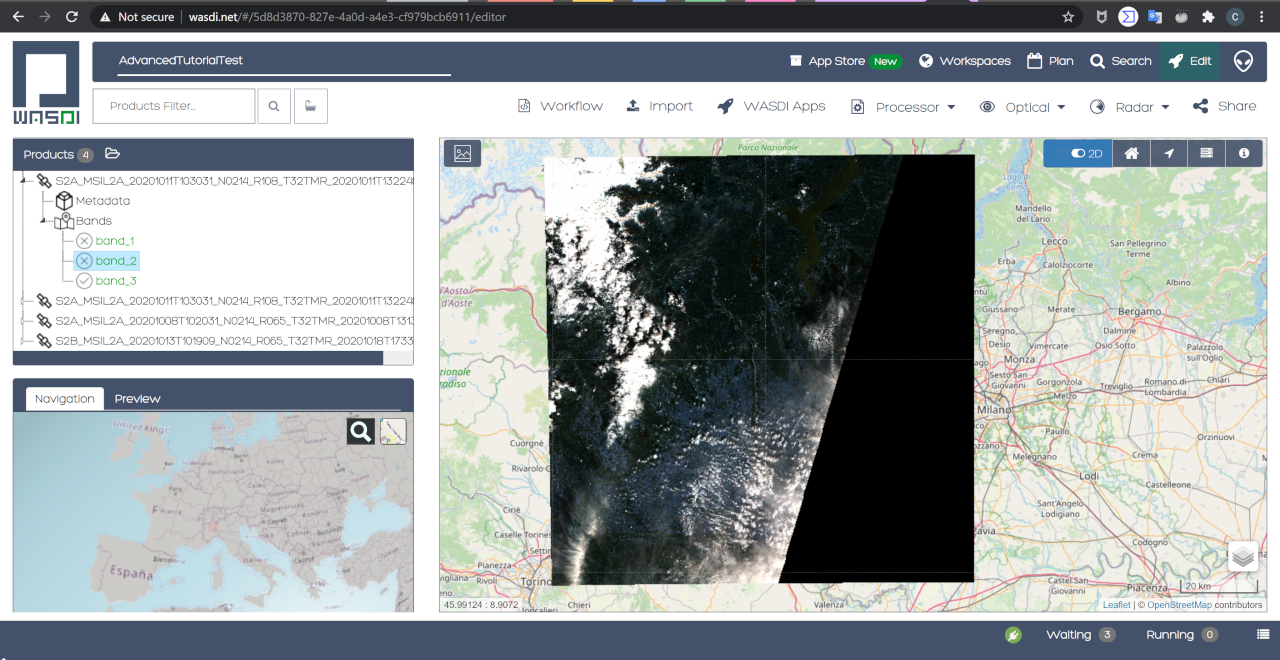

Once the processor is done, we can go to the web UI and open the final result:

To wrap up, you can download the complete code from here: myProcessor.py

Creating a help file

You can create a manual for those who are going to use your processor by adding a file called readme.md to your project. As you can see, it is a markdown file that, once the processor will be deployed, will be rendered to the users.

In the help, it’s a good idea to describe what the processor does and how to use its parameters. This is an example you can copy and paste in your file:

# WASDI Advanced Python Tutorial

This processor searches for Sentinel-2 images and extract an RGB GeoTIFF from it.

## Parameters

Parameters are in this form:

{

"BBOX": "45.9,8.5,45.7,8.7",

"MAXCLOUD": "50",

"DATE": "2020-10-25",

"SEARCHDAYS": "20",

"PROVIDER": "AUTO"

}

where:

- BBOX is the bounding box represented as a string with the format: "LATN,LONW,LATS,LONE"

- MAXCLOUD is an integer representing the maximum cloud coverage (percent)

- DATE is a date for the search

- SEARCHDAYS is the maximum number of days to search in the past, so the search will be performed on the BBOX and in the period [DATE - SEARCHDAYS, DATE], and for images with at most MAXCLOUD% cloud coverage

- PROVIDER is the data provider: use "AUTO"

Check your file locally, you’re going to use it in a moment. If you wish, you can download it from here: readme.md

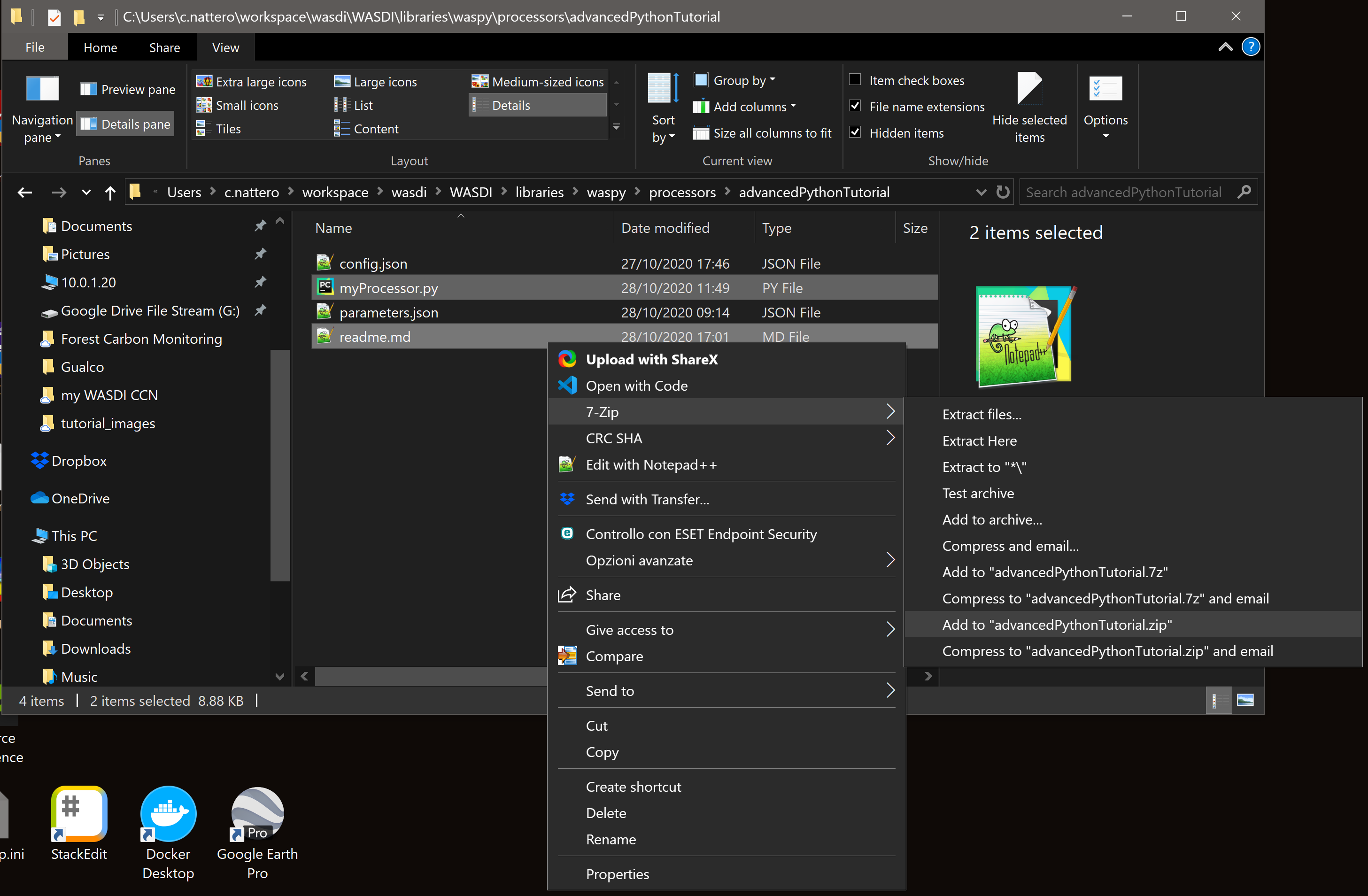

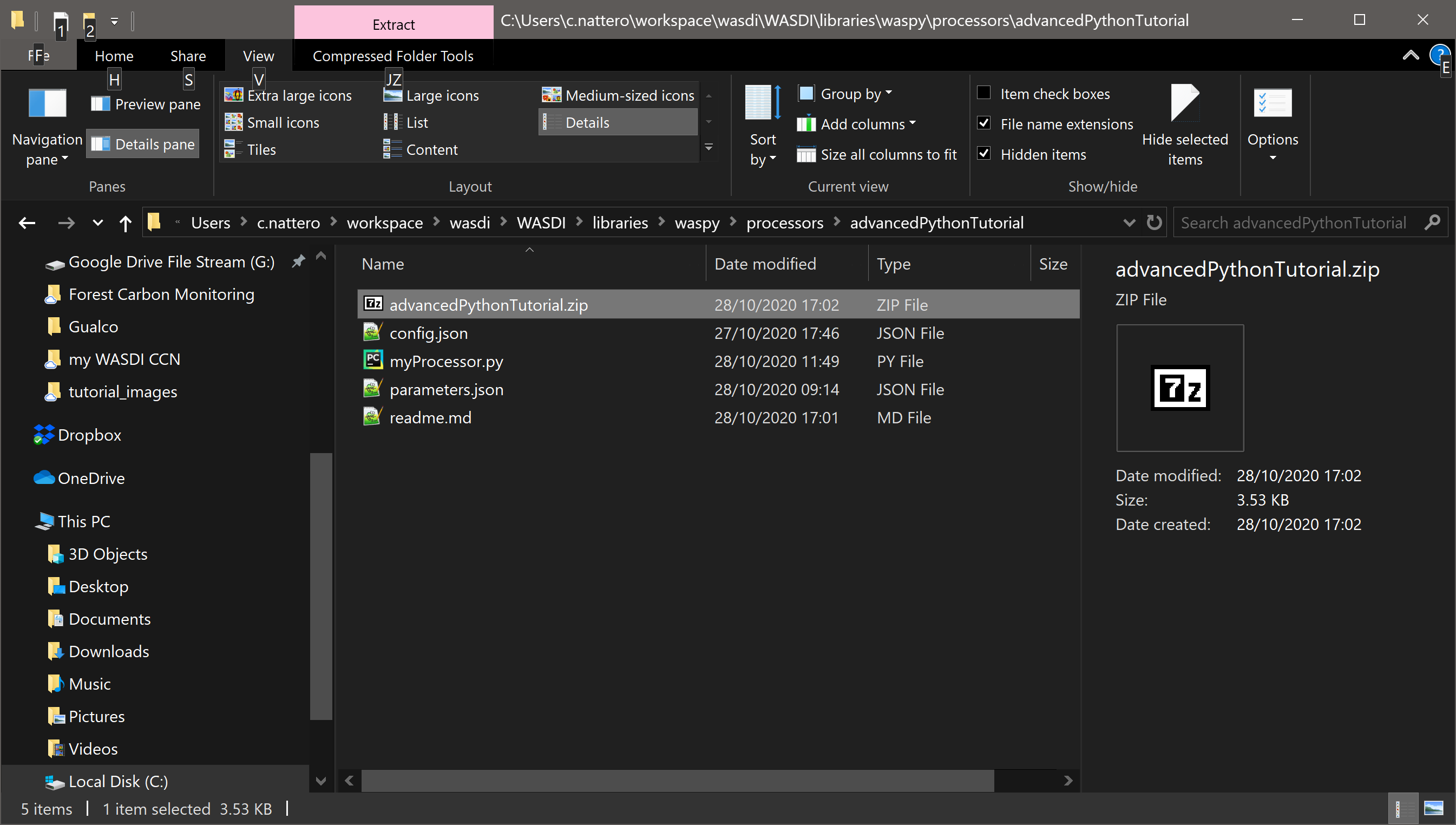

Deploy the processor on WASDI

Now go to the folder containing your processor, create a zip file containing only the following two files:

Pay attention: parameters.json is not necessary, and it is definitely safer not to add config.json

Let us stress the latter once more: do not include config.json in the zip!

You may call the zip file advancedPythonTutorial.zip if you need a suggestion, but the name really makes no difference.

Note: in a more realistic situation, your processor would probably consist of several files, directory and additional ancillary data (e.g., a DTM); in such a case, be sure to:

make the run method in myProcessor.py the entry point

include every relevant file in the zip archive

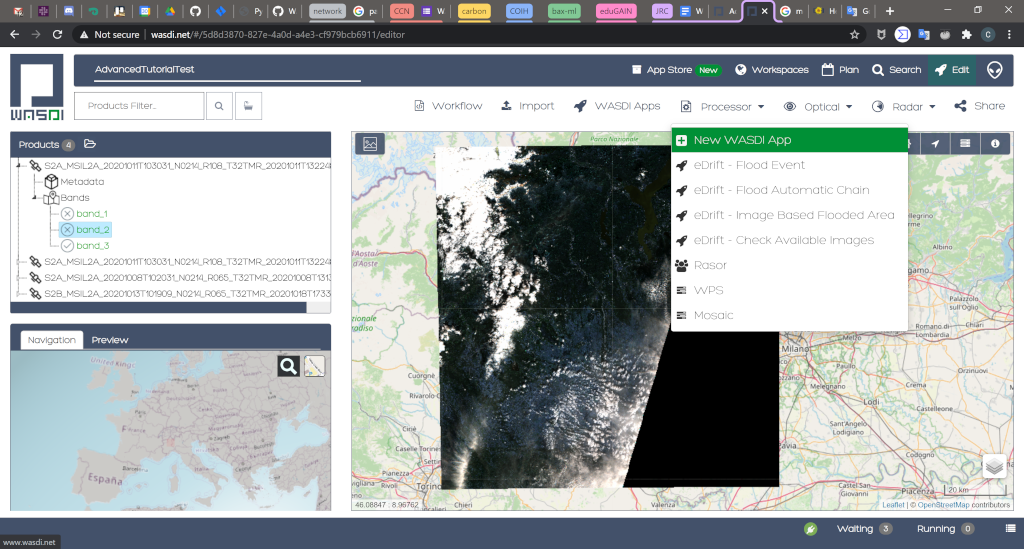

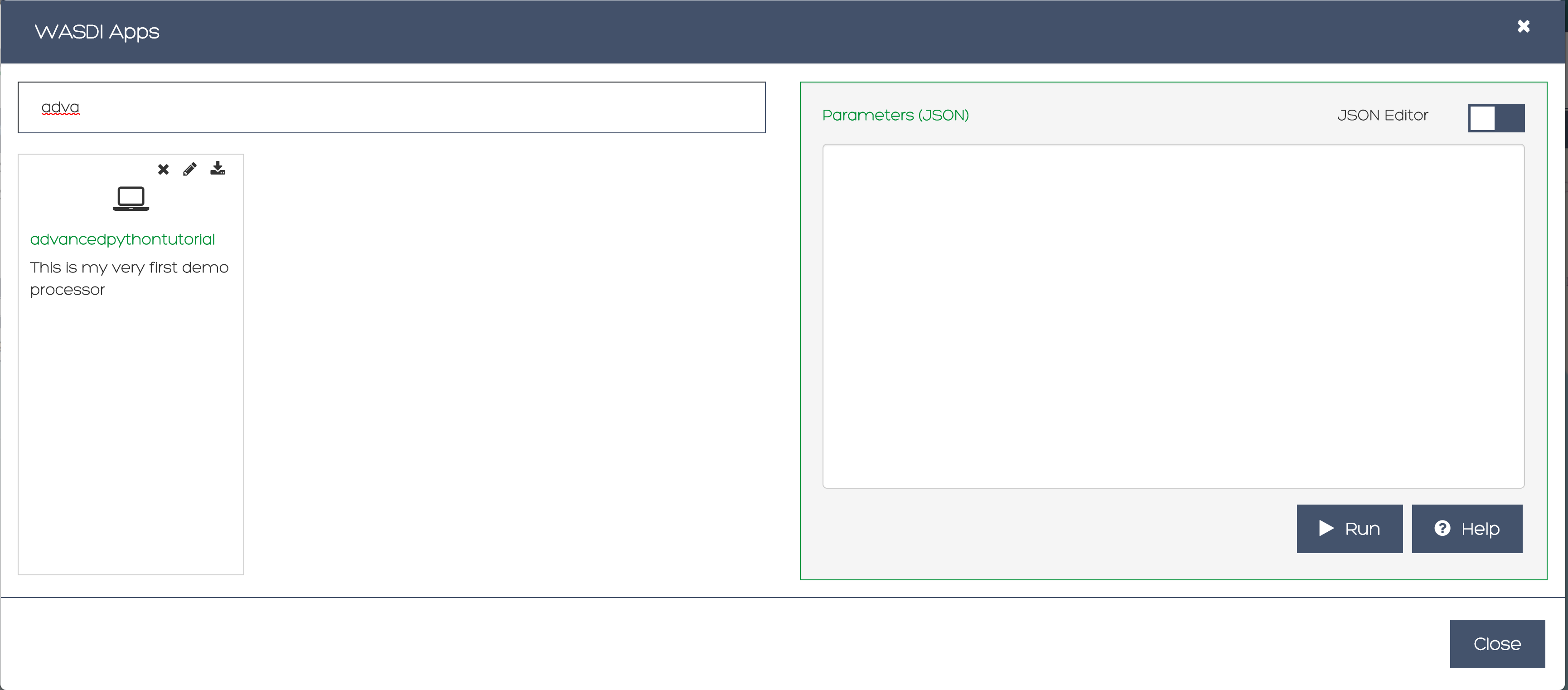

Now go to the WASDI web UI, make sure you are in editing mode (i.e., you have a workspace open). Clic the Processor menu, clic New WASDI app.

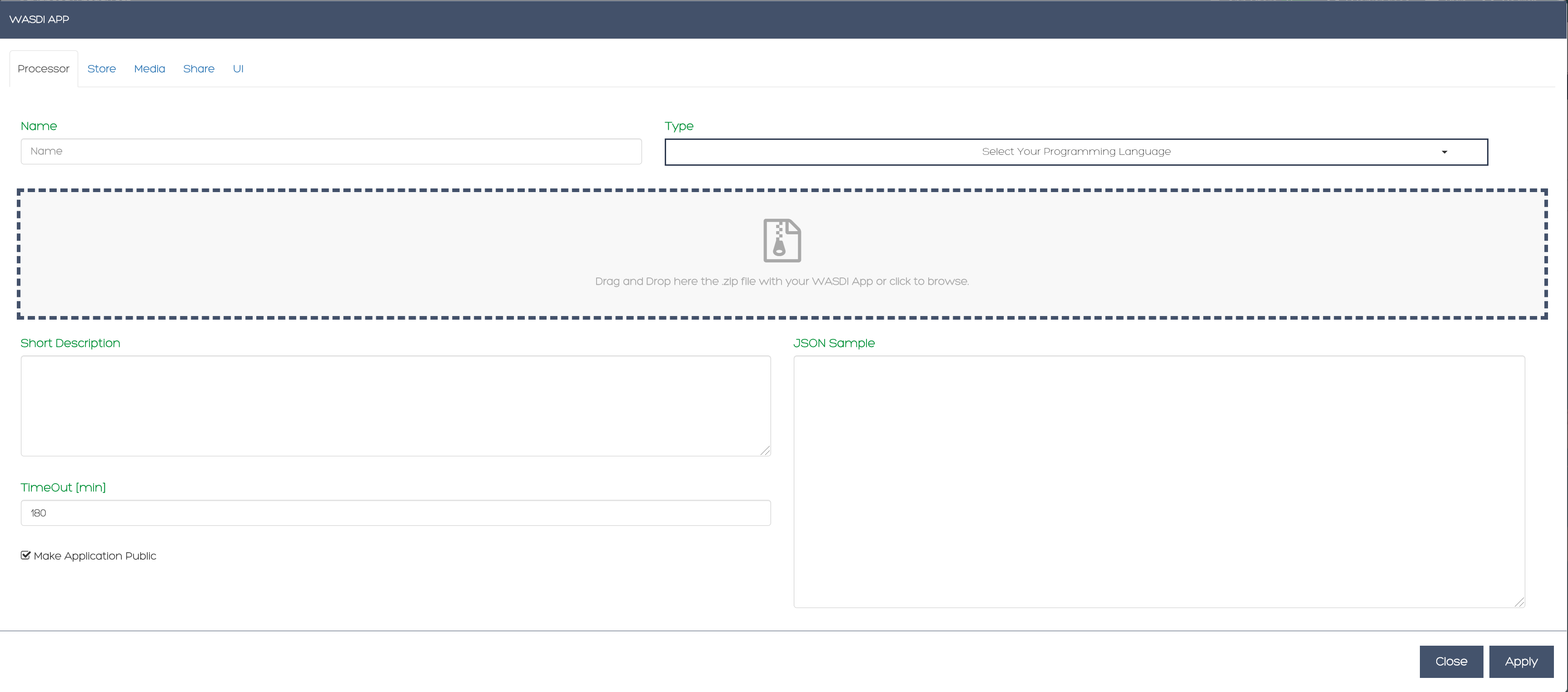

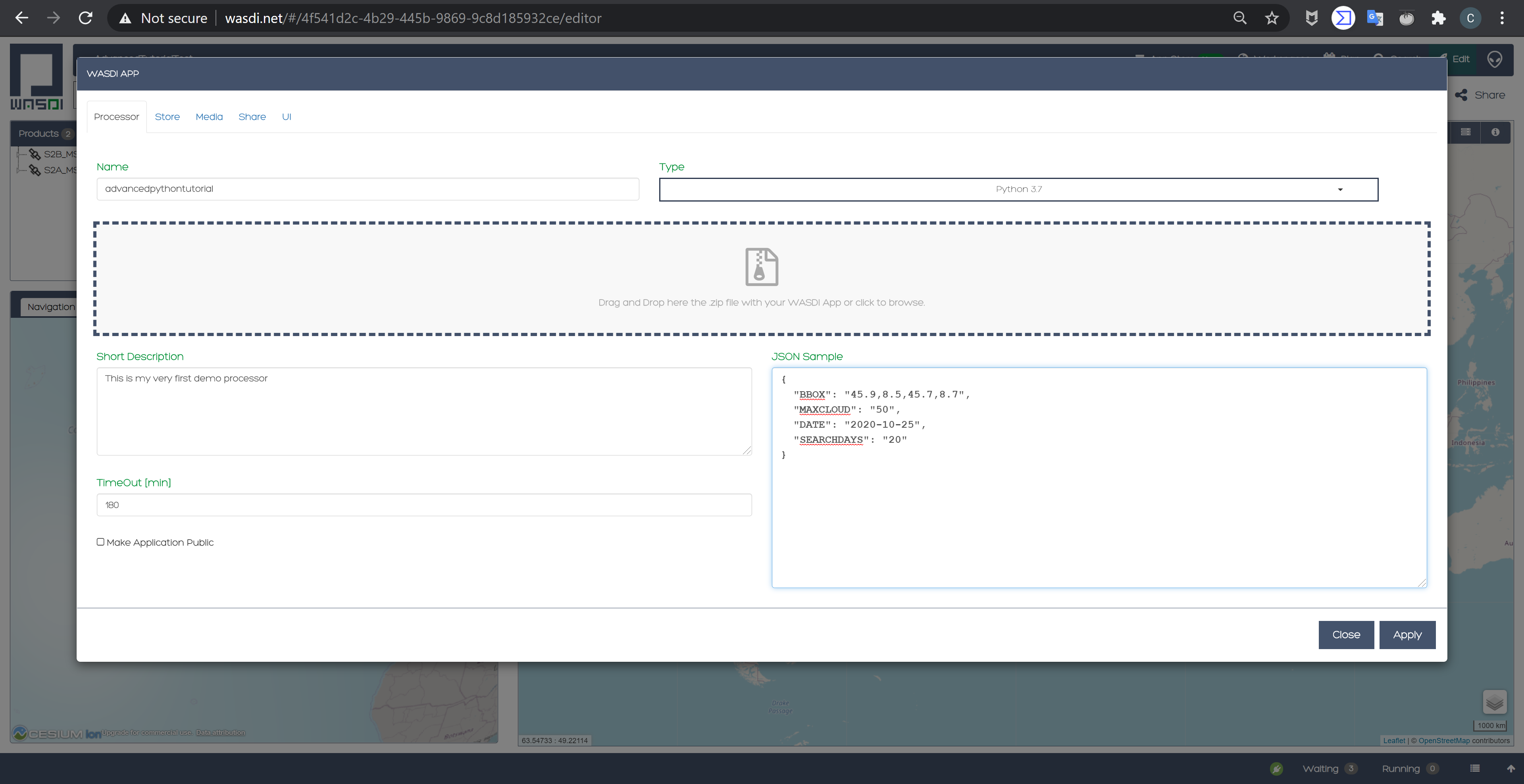

A dialog opens:

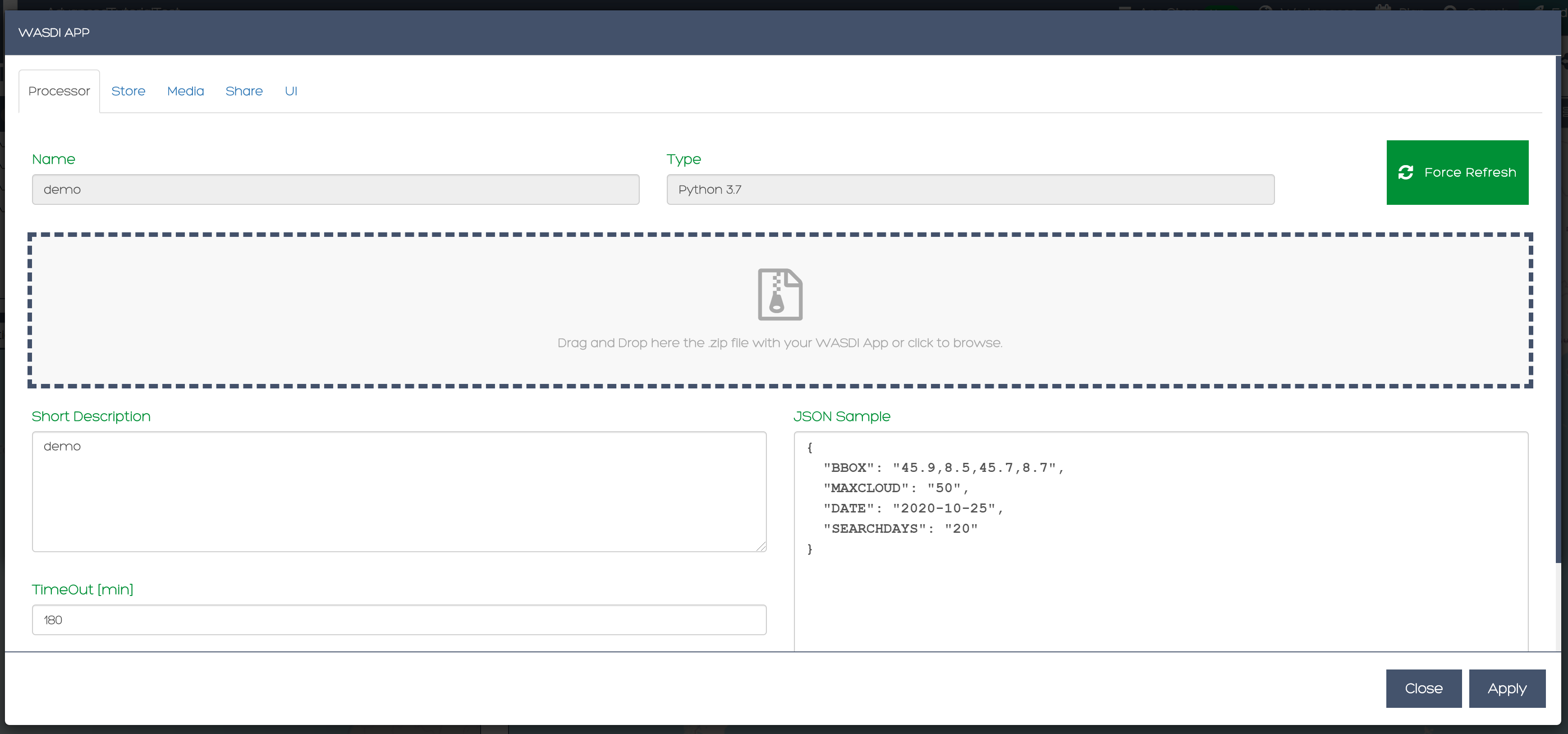

In the dialog:

give your processor a name (e.g., advancedpythontutorial). It must be one small case string

select Python 3.7 as Type

write a short description, e.g. “This is my very first demo processor”

leave the TimeOut with its default value (180)

paste the content of your parameters.json into the JSON sample

make sure you uncheck the Make Application Public box (yes, it’s definitely a nice processor, but we are going to have plenty of copies of it… ;-) )

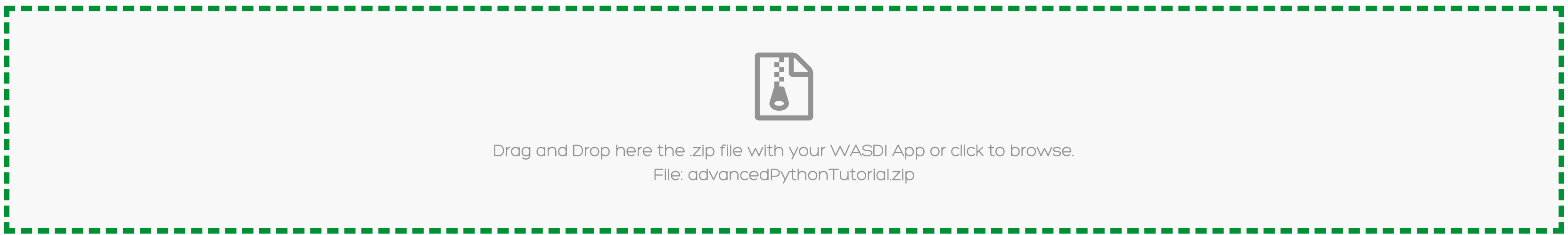

drag and drop your newly created zip file into the area for download

Are you done? Click Apply!

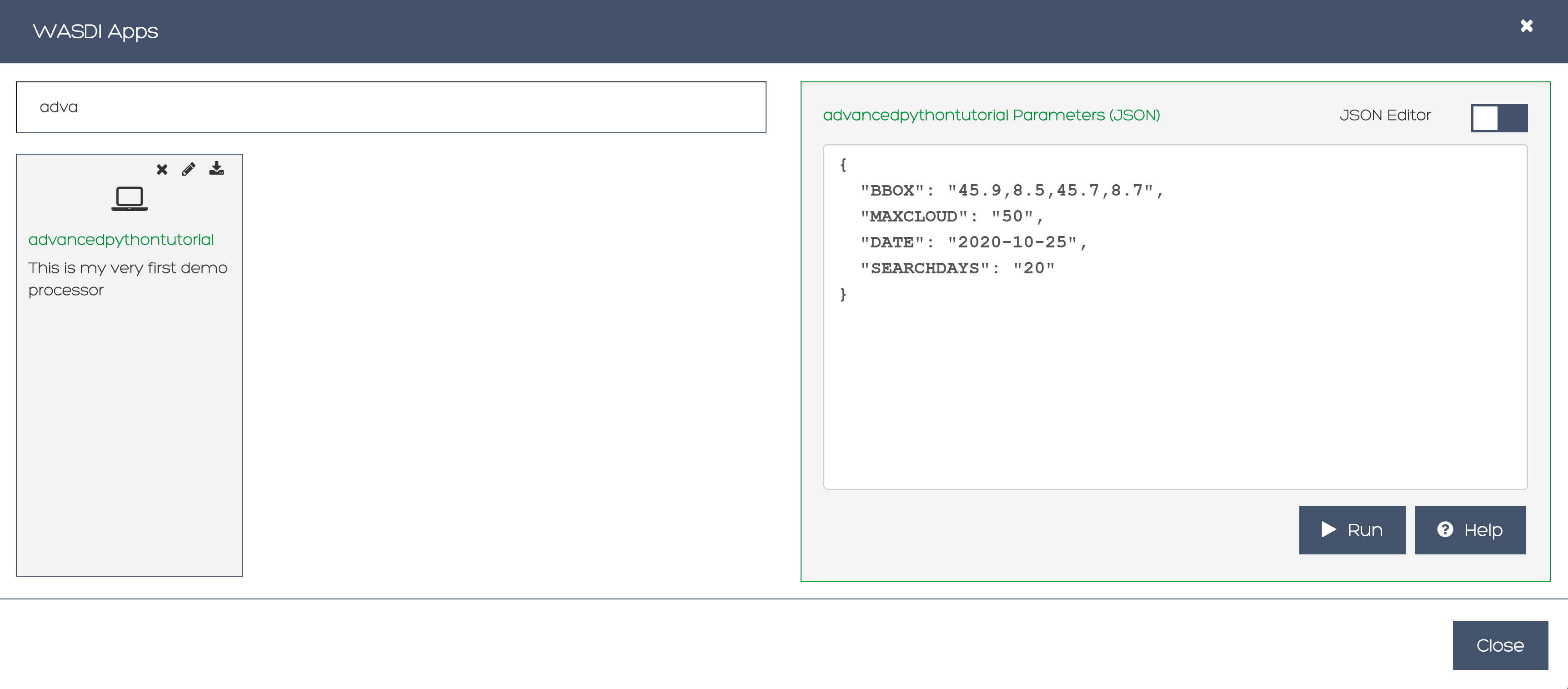

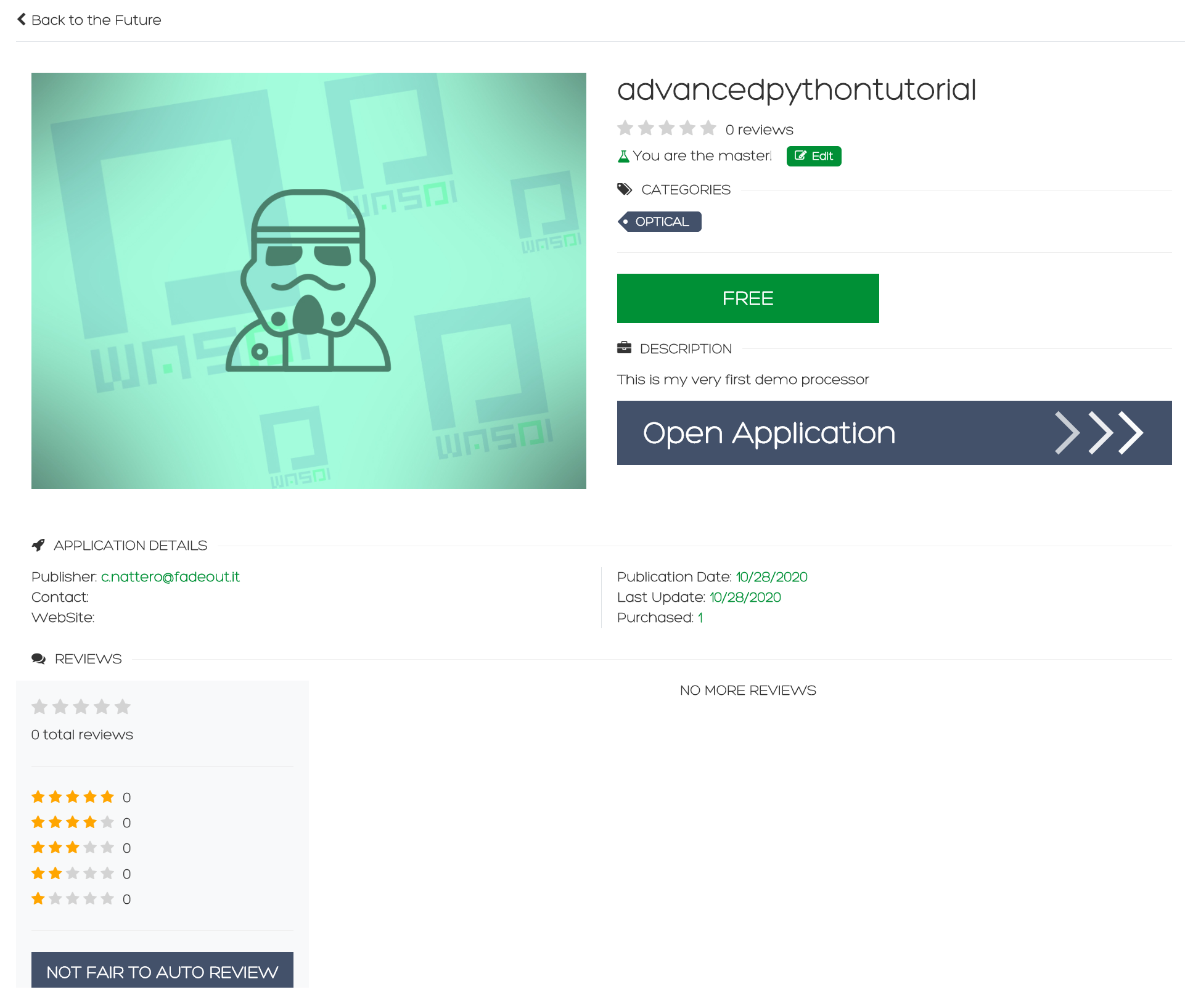

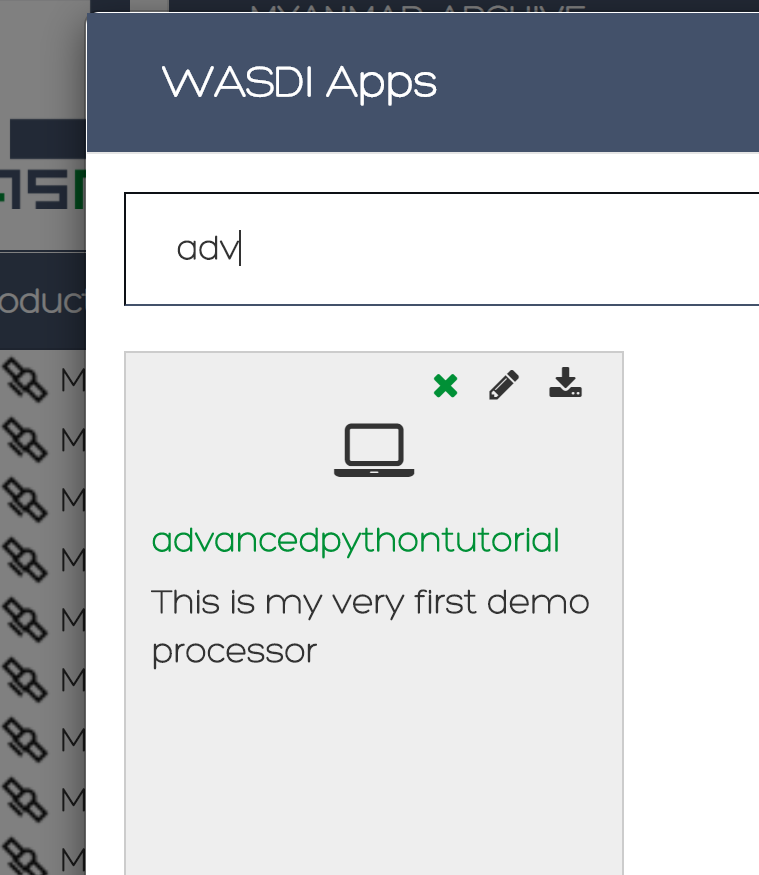

The processor is uploaded to WASDI and automatically deployed. Give it a moment and then click on WASDI Apps. Start writing the name of the processor to search for it.

Select it, and your JSON demo will be displayed. From here you can run it!

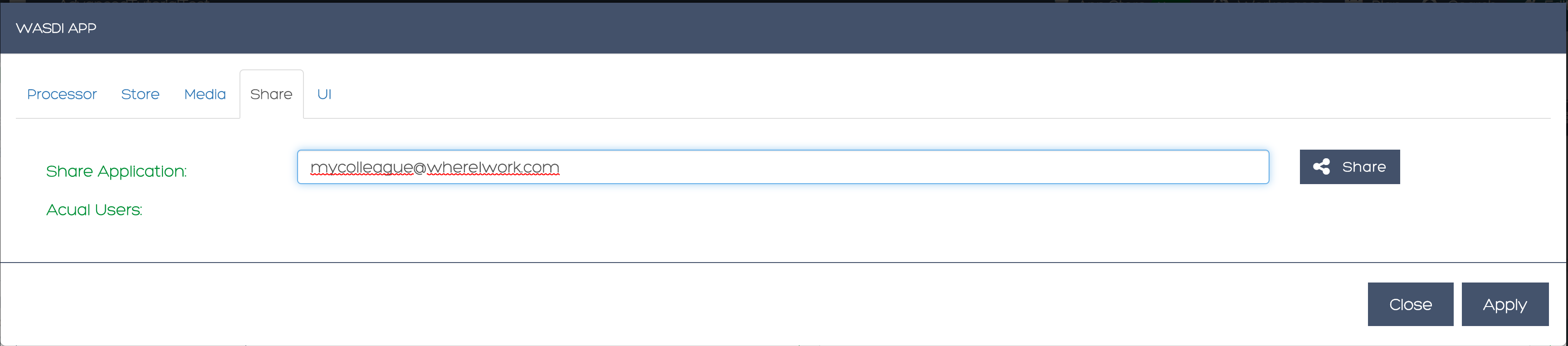

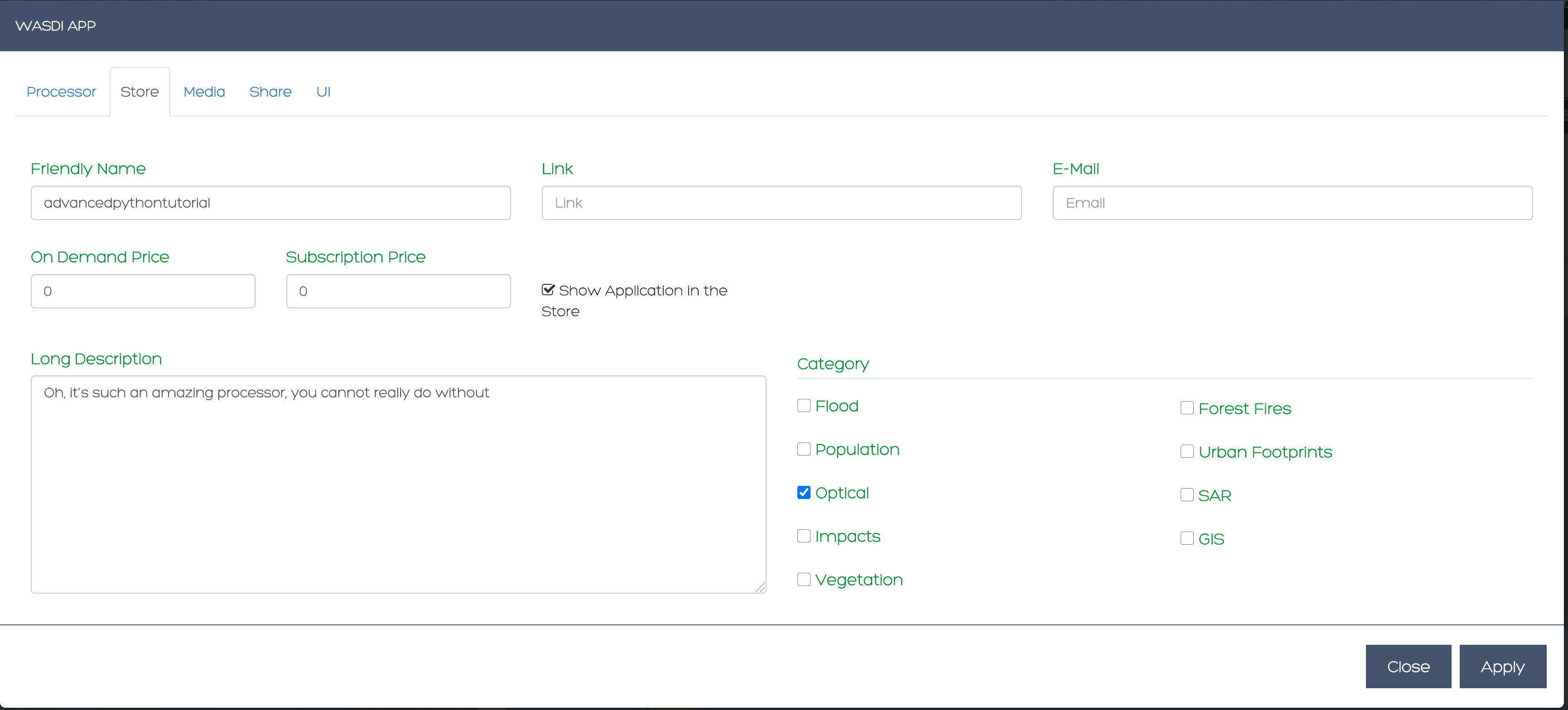

Turn the processor into an app on the marketplace

Well, well, you did great! Now it’s time to let others use your processor (in a not too distant future, you will even be able to monetize your processor by selling its usage): enter the WASDI app store!

Go back to the apps, search for advancedpythontutorial, select it, and clic on the pencil icon to edit its properties. .. image:: ../_static/python_tutorial_images/editYourApp.png

Edit your app You will see that the dialog has some more other than the one we took care of. Now, we are going to see all of them in details:

Processor

Store

Media

Share

UI

Processor tab

We already discussed its usage, but there are still some tweaks we can do here. If you ever needed to edito,one or more of the files involved, simply make a zip containing just the files you need to modify, drag and drop it as usual, and click apply. Of course, you can always change any other propriety you wish, from here. Moreover, there are three cases in which you wish to click the Force refresh button:

you added new pip packages. If you wish to use other packages, you need to write them down, one per line, in a text file called pip.txt. Add the file to the zip and deploy it

you need additional system packages installed. If you need to install additional packages using apt (your code runs on a Ubuntu distro), add a text file called packages.txt and list the packages you need, one per line. As in the previous case: add the file to the zip and deploy it

you updated the wasdi lib

Store

Here it’s where you can choose to show your application on the marketplace. You can give it a more friendly name, add a link and an email address for the users to reach out to support, add prices for the on demand and subscription-based usage modes, write a longer and nicer description, flag some categories, and, above all, flag the box to show your application on the app store!

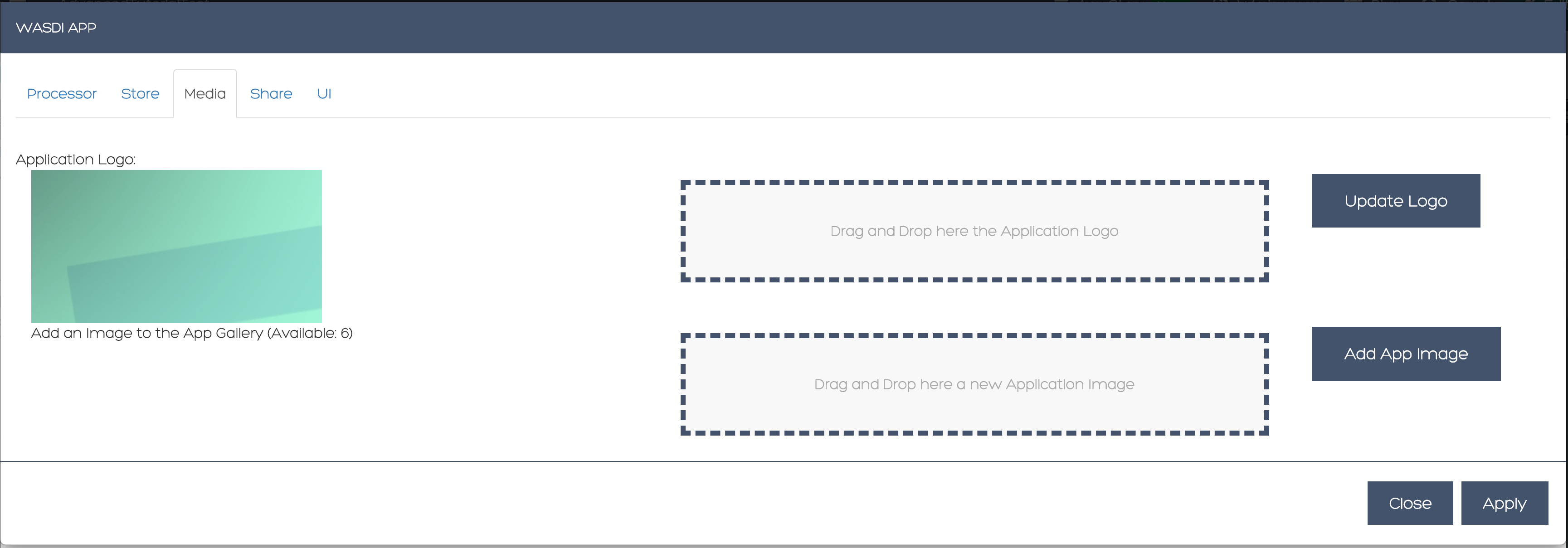

Media

Here you can add a logo and an image for your application

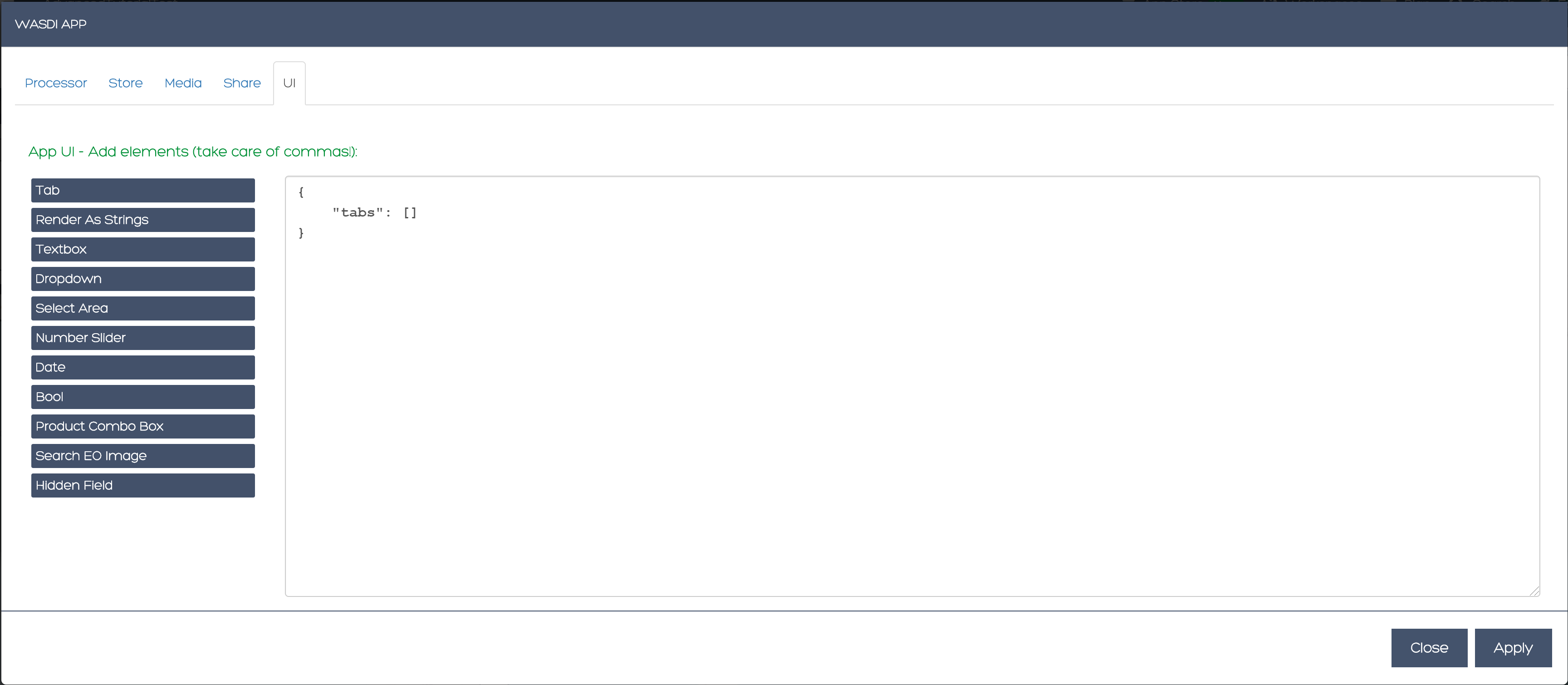

UI

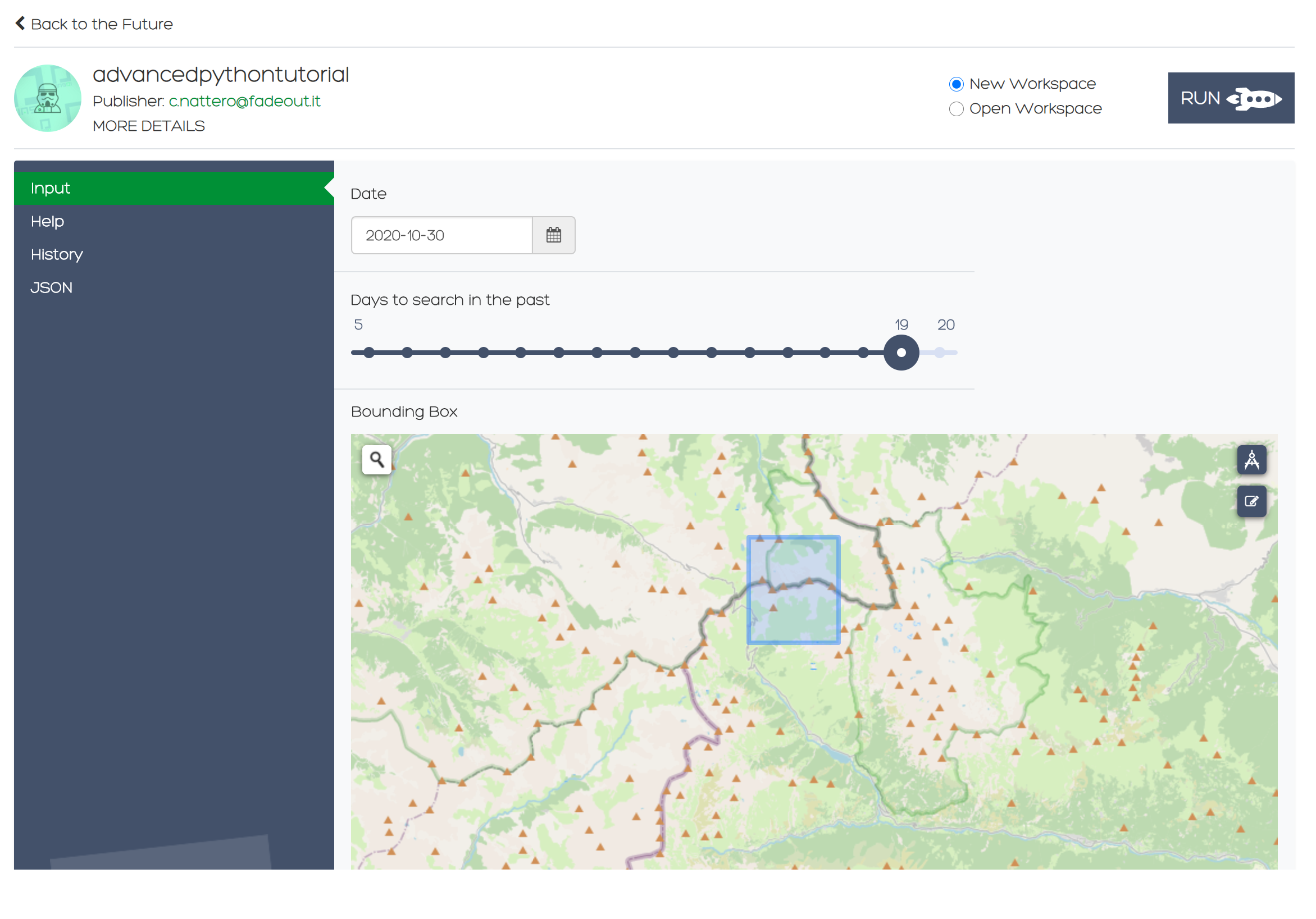

This is where magic happens again: the WASDI interface generator! Using a JSON you can describe a web user interface, which will generated automatically for you. You can fiddle around and you will learn how to use, but let’s make the UI for our processor together.

Click to put the cursors inside the curly brackets, before “tabs”, then click Render As Strings

move inside the square brackets after “tabs” and use the Tab button. Name it “Input”. Remove the trailing comma (or the JSON will not be valid) before the last closing square bracket. Click between the square brackets of your newly created tab.

Use the Date button. Call the parameter “DATE” and mark it required. Click after the comma at the end of the DATE parameter block

Use the Number slider. Call the parameter “SEARCHDAYS”, mark it required. Give it a description. Give it boundaries and a default value (e.g., 5-20, default: 10).

Use the Select Area button. Call the parameter “BBOX”. Mark it required.

Use the Number slider. Call the parameter “MAXCLOUD”. Mark it required. Bounds are 0 and 100. Default: 30. Give it a description.

Check there are no trailing commas!

This is what it should look like in the end (you can copy paste this, if you did not manage to build your own):

{

"renderAsStrings": true,

"tabs": [{

"name": "Input",

"controls": [{

"param": "PROVIDER",

"type": "dropdown",

"label": "Data Provider:",

"default": "AUTO",

"values": [

"AUTO",

"EODC",

"SOBLOO",

"CREODIAS"

]

}, {

"param": "DATE",

"type": "date",

"label": "Date",

"required": true

}, {

"param": "SEARCHDAYS",

"type": "slider",

"label": "Days to search in the past",

"default": 10,

"min": 5,

"max": 20,

"required": true

}, {

"param": "MAXCLOUD",

"type": "slider",

"label": "Max cloud cover (percent)",

"default": 30,

"min": 0,

"max": 100,

"required": true

}, {

"param": "BBOX",

"type": "bbox",

"label": "Bounding Box",

"required": true

}

]

}

]

}

If you wish, you can download the UI description as a JSON file from here: UI.json

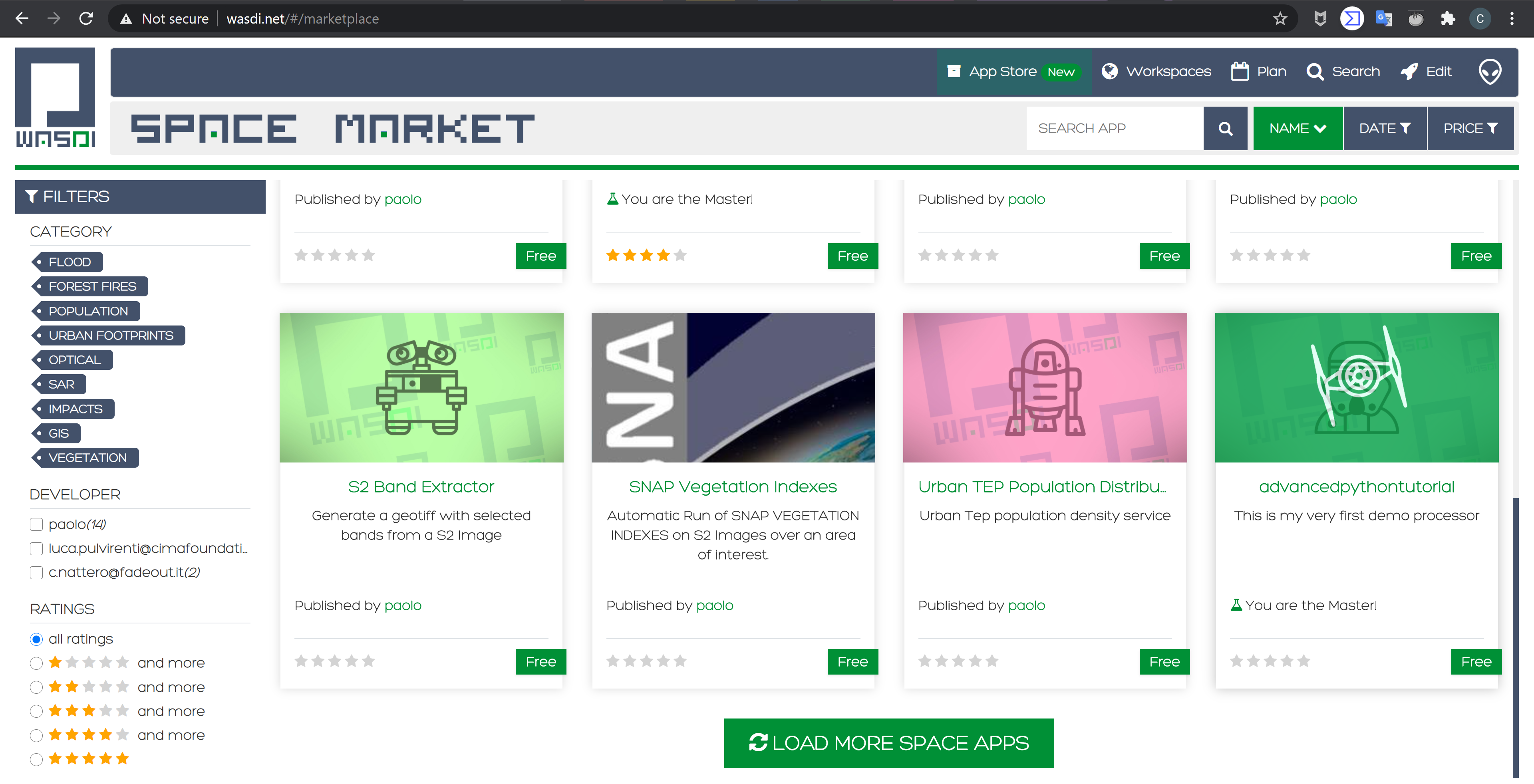

The app store

Now go to the app store, and try to use your app from there. To find it, you can filter using your user, or search using the name.

Once you opened the app presentation page,

The app in the store open the application to test it for real.

There you can see the interface you just described. Use it, and to see if it works as expected

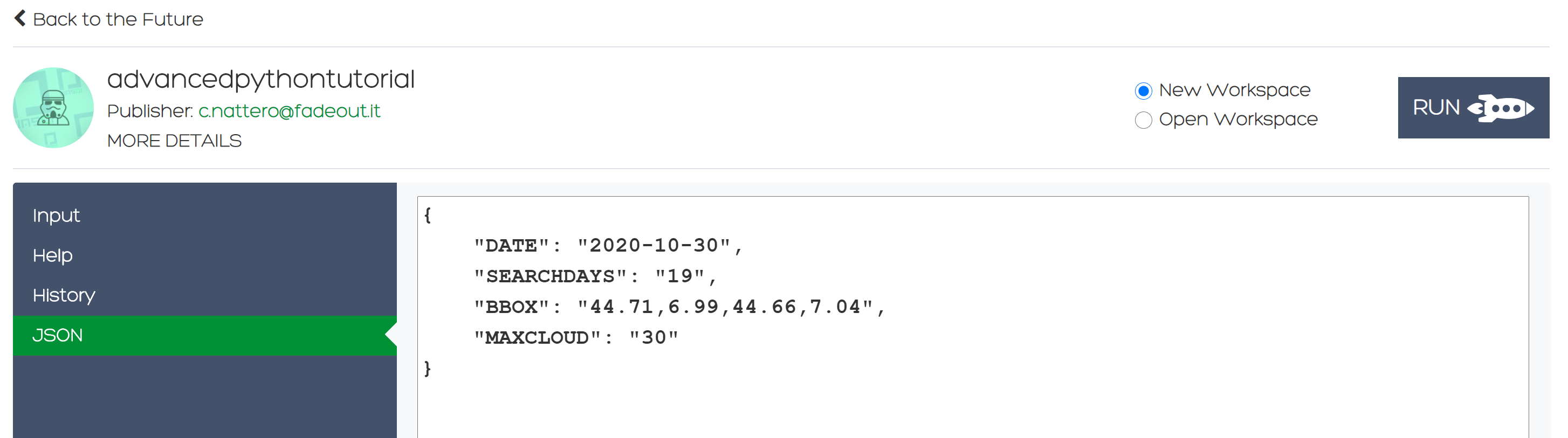

before running the processor, you can also check the JSON that will be generated automatically with the parameters your processor need:

Feel free to play with your processor and tweak it.

Delete your app

Are you done? Here you are two sad facts:

this processor is not a milestone in the history of remote sensing

Santa Claus does not exist

We cannot change the second, but we can solve the first by deleting the processor: got to the editor (i.e., open a workspace), search for your app in the WASDI apps menu, clic on the x symbol to delete the app

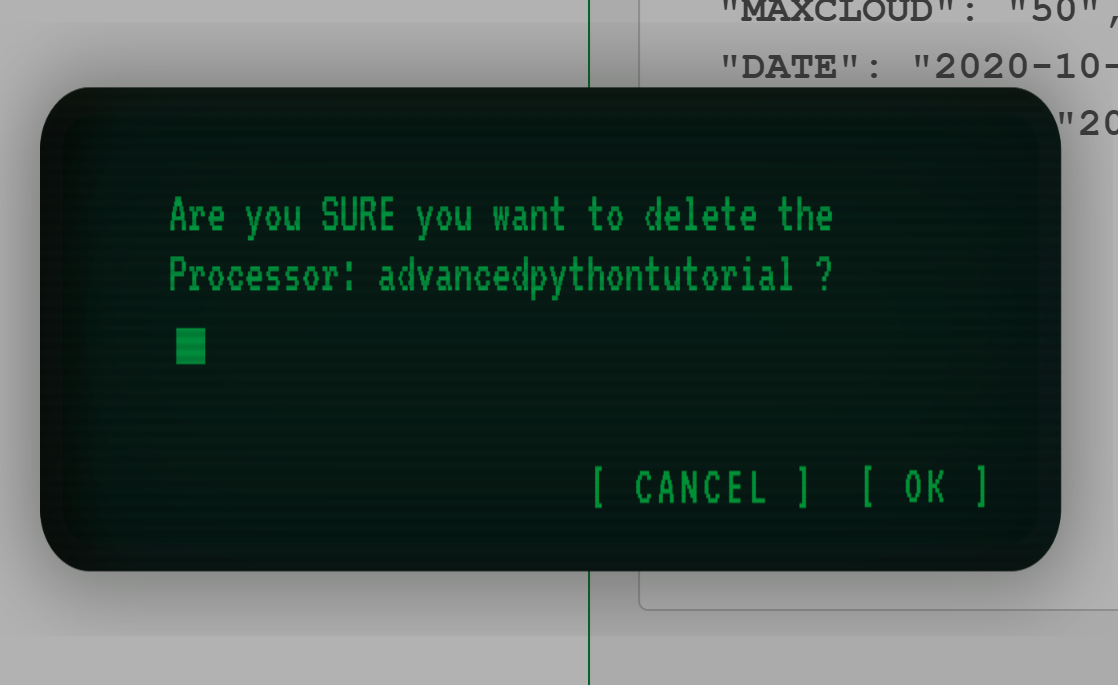

That’s how you delete a processor Clic OK to confirm that you want to delete it

Confirm processor deletion That’s it, now you know how to manage the entire lifecycle of a WASDI app!

Have fun, and let us know your thoughts